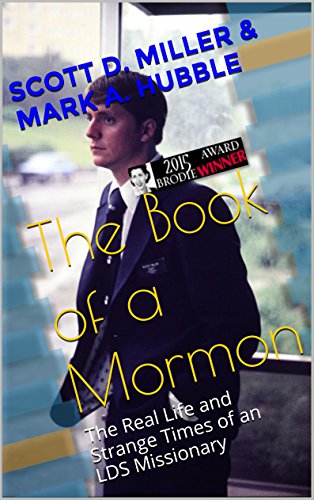

Who hasn’t come into contact with Mormon missionaries–the mostly very young, mild-mannered and smiling men dressed conservatively in a suit and tie, who we are to address as elder? Over the years I have read enough about the ascetic and grueling lives of Mormon missionaries to feel quite strongly that they deserve politeness and compassion from the people they approach with their scripted message, even when one has no intention of joining their church and doesn’t fancy being the subject of proselytization. Scott D. Miller’s memoir, The Book of a Mormon: The Real Life and Strange Times of an LDS Missionary, paints a deeply human picture of these young missionaries–one that evokes empathy–while offering a searing critique of the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

Originally from the warmer, sunnier pastures of southern California, Elder Miller finds himself assigned to serve a two year stint as an LDS missionary in grim, frosty Sweden. One of the most engaging aspects of this book is how a young Californian from a tightly-knit Mormon community sees Sweden of the 1980’s. There is culture shock aplenty. Swedish society is largely secular and socially liberal, the landscape is inhospitable, the architecture and everyday life seems plainly functional–drab, bland and sometimes pretty bleak. Most Swedes seem to either resent or dismiss, and sometimes mock, the dogmatic religiosity that these Mormon missionaries represent. Though perhaps none mocked Mormonism as thoroughly as Mark Twain did–Miller quotes the iconic American author as referring to the Book of Mormon as “chloroform in print.”

Most inhospitable, and at times outright brutal, is how the LDS leadership in Sweden treated their own missionaries. Miller explained that prior to becoming a missionary, Mormonism to him represented a family-friendly, community-oriented lifestyle, where you could always rely on other Mormons to be supportive of you in difficult times. You were never alone. (“Charity is the currency the Mormon Church runs on…”) In contrast, the church leadership in Sweden was ruthless with their young missionaries, most of whom were twenty years old or younger. According to Miller’s portrayal, being a missionary was tantamount to working in a high pressure, controlled and militaristic environment as a salesman or soldier of religion. Nothing counted more than how many Swedes you proselytized (and ultimately talked into baptism).

Swedes were resistant to this message and the young Elder Miller soon realized that if you stood little chance of converting them, you could still make the best of the situation by being human, empathetic and Christ-like in how you approached people and met them at whatever juncture they happened to be in life. Some of the locals that Elder Miller met were simply lonely–like the old woman who was happy to welcome Miller and his companion into her home with a warm dinner of soup and bread. She even patched up the tear in Elder Miller’s pants. She was hospitable and clearly yearned company, but was far less interested in baptism.

Several of the missionaries featured in Miller’s memoir are quite endearing–sometimes for their social awkwardness and vulnerability. One of Miller’s companions struggles with the constant indignities and pain of colitis. The only person to show him any empathy and compassion is Miller. Another companion develops romantic feelings for Miller and wrestles with his sexual orientation. (“I keep praying, but nothing happens,” young Bernie explains his hope to be “cured” through divine intervention.) It is the Church leadership’s inability to respond compassionately to the vulnerable that was the most jarring aspect of this book. As Miller notes: “The church exists to serve its members–particularly its most vulnerable, children–not the other way around.”

Miller’s memoir is not merely a bitter reflection of a very difficult (though formative) period in his youth. In fact, it is not primarily that at all, even though his mission in Sweden resulted in him drifting away from the church. Many of the other characters in the book are vibrant and multidimensional and occasionally, the reader will get morsels of insight, as these young men try to share their faith with a largely secular society. Quoting Werner Heisenberg, for instance, we read: “what we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” Heisenberg is followed by a response from a missionary to an atheist’s conviction that there is no God. “Of course God doesn’t exist for you. Your questions do not allow it,” he responds quite cleverly.

Miller’s memoir is human, thoughtful, nuanced and at times jarring. It’s well worth a read if you are at all interested in the lives of the smartly dressed young men travelling in pairs (and more recently women too) who may knock on your door.

Rating: 4/5

Be First to Comment