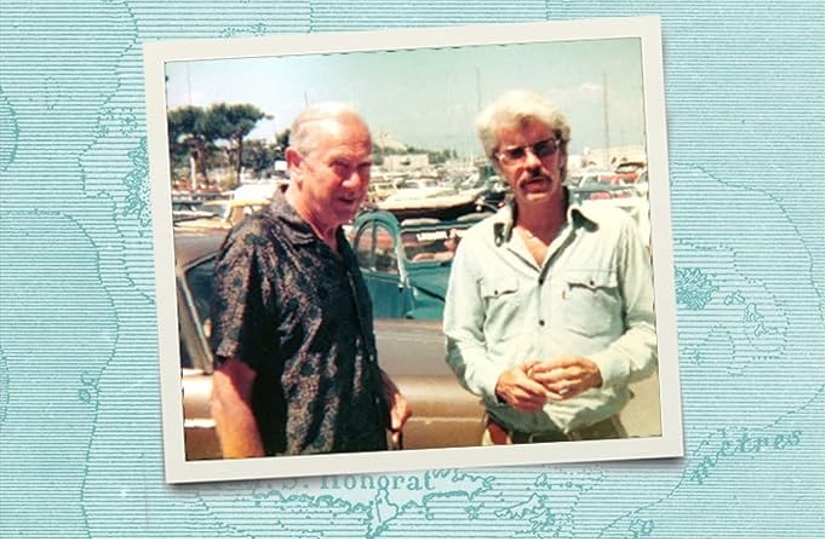

A fledgling novelist in his twenties writes a letter to one of the bestselling authors of the twentieth century. He not only receives a response, but he’s also invited to the author’s apartment for drinks. So begins an unexpected friendship between British author Graham Greene and a young American, Michael Mewshaw, in the early 1970s. It would persist across countries and continents, and evolve over the span of two decades. There’s a significant risk of a novice author being sycophantic in his interactions with such a master of the written word. Yet Mewshaw isn’t obsequious at all — neither in his friendship with Greene, nor in the way the famed novelist is presented in My Man in Antibes. We’re treated to an array of correspondence between the two men. At various times their letters are humorous, self-deprecating, fraught, angry, forgiving and gentle. But this book isn’t an anthology of archived letters with an introduction slapped on at the beginning. It’s a thoughtful and sometimes gossipy story of how a young man from a disadvantaged background gains a foothold in the eccentric and cut-throat world of publishing, and how he sustains a friendship with a famous, but often reclusive and guarded author.

We’re given vignettes from Mewshaw’s unhappy childhood in Maryland near the beginning of this book. His mentally ill mother treated the young Michael in cruel and abusive ways. His stepfather was a gruff, violent man. If anyone is in need of a reminder that America in the forties and fifties had a seedy side and that slums with similar social problems to those seen today existed then as well, read the first chapter of Mewshaw’s book. He points out that Greene had a miserable childhood too, deeply unhappy as he was in a harsh school environment where his father served as principle. But Greene also came from a middle-class family, while Mewshaw’s dysfunctional parents were of the troubled working class. He saw a level of violence at home and in his community to which no child should be exposed. One of the teenage Mewshaw’s escapes, however, proved to be the novels of Graham Greene. It’s no surprise that gritty, suspenseful Catholic novels like Brighton Rock or The Power and the Glory would appeal to an east-coast working class Catholic boy coming of age in the fifties. And what he may have known then of Greene’s adventurous, globe-trotting life would have appealed just as much.

Given his economically disadvantaged background, his experience of emotional and physical abuse, and the lack of family support, what chance did the young Mewshaw have of launching a writing career, getting a Fulbright and becoming friends with a literary icon of his time? Before even publishing his first novel, with barely a cent to his name and having just met his new wife, he achieves the near impossible. He travels to France on a Fulbright, writes to Greene and he receives a response. It’s a brief reply and Greene doesn’t think it likely that they could manage to meet due his upcoming overseas travels. Yet a busy, celebrated author took the time to respond to a young fan. For all that has been written of Greene’s various trespasses in life, he responded diligently to letters from readers.

It took a second letter to seal the deal. This time Greene invited Mewshaw and his wife Linda to his apartment in the French coastal town of Antibes. To Greene’s credit, he lived in decidedly modest surroundings, despite his celebrity status — so much so, that even the young Mewshaw took note. Greene complained of neighbours barbecuing on their small balconies all around him, with the smell of other people’s sizzling meat permeating his place late into the night.

He was, of course, an affluent man with not only a simple apartment in Antibes, but a flat in Paris, a villa on the island of Capri, and then in the last years of his life an apartment in Vevey, Switzerland, overlooking Lake Geneva. Based on this initial meeting with Greene and then on subsequent ones too, we get the impression of a man who can be socially awkward, as well as both withdrawn and sometimes oddly talkative — even to the point of oversharing. He can come across as shy and perhaps vulnerable, but also has the capacity to make sweeping statements, curt judgments and jokes both at his own expense and at others. Mewshaw also notes the striking paradox of a man who had travelled the world and went as far off the beaten path as possible, while never learning to drive and being poor with directions.

Drinks with Greene in his apartment isn’t a one-off encounter. He invites Mershaw and his wife for dinner to a restaurant in the historic town of Mougins, where they eat Shepherd’s Pie — which we learn is Greene’s favourite dish. Linda then prepares dinner for Greene in their small, mice-infested rental cottage in Auribeau–sur-Siagne and later they dine with Greene’s lover, Yvonne Cloetta, as well. In later years, Chez Félix au Port in Antibes became a place where they have many discussions over drink and food. In between the in-person encounters, Mershaw and Greene exchange dozens of letters. Their friendship and their ability to keep up with each other’s ever-changing postal address is the constant in a life that is semi-nomadic for both. Mershaw doesn’t emulate every aspect of Greene’s existence, especially not his serial infidelities. But he does gravitate to a sense of being uprooted and he struggles with depression, as does Greene — the latter in a particularly acute way. Mewshaw can’t fathom settling down and buying a home in Austin, Texas, where he eventually becomes a tenured professor. Instead, he lives for months at a time in various rentals, including first in a converted chicken coup in Charlottesville, then later in Key West, Paris, southern France, Spain and Rome. He flees the US for Europe whenever he can and his wife consents to instability. The life of travel and relocation continues even after their first son, Sean, is born. Once Marc, their second son, arrives the family’s life becomes somewhat more rooted in Rome.

My Man in Antibes humanizes Greene both through personal anecdotes, as well as by exploring aspects of his life that though recorded in the various biographies and autobiographical works are overshadowed by the more salacious details. Greene had serial affairs with women, including with married women. He never divorced his wife Vivien Dayrell-Browning, due to her devout Catholicism, but instead separated and became distanced from his two children to pursue many relationships and romantic encounters. He had an affair with Catherine Walston, the wife of a Labour politician, which lasted about six years. Greene enjoyed extended stays in Ireland and in continental Europe with Catherine, with the full knowledge of her husband and her children. A few years later he began a relationship with Yvonne Cloetta, wife of the diplomat-turned-businessman Jacques Cloetta, which would last for decades. They had met in Cameroon in 1959. Her husband spent most of his time in Africa, while Greene and Yvonne essentially lived as a couple in Antibes, on the island of Capri, and then in Switzerland. When Jacques returned to Europe in the summers to be with his wife, Greene would leave the scene. He used this time each year to tour Spain with Father Leopoldo Duran, a Catholic priest and longtime friend.

Mewshaw notes how Greene supported his wife and his various lovers after these relationships had ended. He assisted them financially, sometimes even buying them homes. His relationship with Yvonne seemed to be a genuinely loving and life-giving one. Greene staunchly supported her adult daughter when she went through a very nasty and delicate personal problem in her life, to the point of risking and sacrificing his own interests and well-being. He also showed much affection to Yvonne’s dog, Sandy, who often sat on his lap while he dined with Mewshaw. Greene followed developments in Mewshaw’s personal and professional life with interest and care. He was happy to hear of the birth of their children, he supported Mewshaw’s fledgling writing career and offered gentle reassurance in his letters in moments of turbulence. Mewshaw’s book softens the sharper edges around Greene’s life and personality.

What was Mewshaw looking for in his friendship with Greene? Only Mewshaw himself can properly answer that question, but I feel he sought more than discussion with, or inspiration from his favourite author. Two men in this book serve as something akin to father figures to Mewshaw. Greene is one of these and the other is Philip Mayer — the author and journalist who lets Mewshaw live in his grand villa in Auribeau whenever he and his wife Claire are away, in exchange for Mewshaw playing tennis with him when he is there. In later years, the two head off on a road trip to Spain together and the book itself is dedicated to the memory of this warm, generous, caring and eccentric man. Greene didn’t offer the same jovial warmth, but he showed care and concern for Mewshaw in his own way.

What did Mewshaw bring to Greene’s life or what did he hope to bring him? Mewshaw had an intrinsic desire to cheer him up. He did so by sharing some immensely amusing stories — perhaps mostly true, but certainly embellished in the telling with literary flair. One of these was how he had almost been robbed of his wristwatch at banana point during a home invasion in Key West, Florida. The burglar carried a blackened banana as he hovered above Mewshaw’s bed in the middle of the night and tried to steal his watch. “It seems he was carrying a big black mushy one instead of a pistol. At least I assume he had the piece of fruit for that purpose,” writes Mewshaw in his letter. Greene responds:

I liked very much your fruity story. I have intercepted twice the same man trying to open the door to my neighbor in these flats. I think he’s deranged rather than a robber, but that is hardly more encouraging. As a result, I bought in Rue de la Paix a teargas bomb which I keep handy.

That response has in it Greene’s signature economy of language, through which he so effectively communicated paradox.

Equally funny is a vignette that Mewshaw shares with Greene about babysitting author Anthony Burgess’ rascal-of-a-son in Rome, and a disastrous press conference that Burgess once held. Although Burgess, a British expat in the Mediterranean and a Catholic like Greene, lived a stone’s throw away in Monaco, the two men didn’t much care for each other. More precisely: Greene had very little time for the sociable, boisterous and attention-seeking Burgess.

At the heart of the book is a conflict that Greene had with Mewshaw over quite a flattering article he published on him. The piece in London Magazine caused Greene “real horror.” The 1977 profile entitled “The Staying Power and the Glory” is reprinted in full in this book, as are the letters between Greene and Mewshaw that followed. Greene’s horror over what he believed were errors in the piece included mention of how much opium he had smoked before meeting with Vietnamese communist leader Ho Chi Minh during a trip to Vietnam. “I had merely had a couple of pipes of opium in the old town and as my ration was normally ten pipes I was certainly not stoned,” Greene wrote.

He accused Mewshaw of inaccurately sharing information that he had told him during their first visit in Antibes. Greene had shared a great many anecdotes of his travels and did so in various states of excitement. At times without proper context and sequence, they were hard to follow. One of the more amusing ones had been how Haiti’s mad and murderous dictator, Papa Doc Duvalier, had personally arranged to publish and distribute a furious pamphlet entitled Graham Greene démasqué — “exposing” him as a pervert, racist and a spook. Greene retained a copy of the pamphlet in his apartment.

Mershaw pushed back politely but firmly, noting that his wife Linda had the same recollections of that first visit as he did. Part of their exchange touches on the interplay between fiction, journalism and the truth. “I don’t think that any journalist has done worse for me than you who are such a promising novelist,” Greene wrote. Mewshaw responded: “It seems not to have occurred to you that when we talked there were two novelists in the room. I should have kept that fact first and foremost in my mind and not been so gullible.”

Greene’s fury subsided as suddenly as it had erupted. He closed this heated fraught exchange with a brief note suggesting that they forget all about the conflict and move on. They did just that and their friendship persisted for another 14 years, up until Greene’s death at age 86. Greene remained supportive of Mewshaw’s writing and they enjoyed each other’s company whenever they had an opportunity to meet. They spoke about other authors, the travails of writing and publishing, politics, travel and about their own lives. They rarely broached the subject of religion, despite their shared Catholicism. Mewshaw writes:

Being Graham Greene, as rich a prize as that had once seemed to me, entails a cost too great to be borne by anybody except the man himself. For all his frailty, he had incomparable courage and strength. Despite his occasional querulousness and quickness to anger, he had a forgiving soul. Whether he finally received forgiveness himself, God alone knows.

Graham Greene died over three decades ago. The fact that in 2023 a traditional publisher would still agree to release the biographical account of a contemporary author’s friendship with him speaks to the staying power of Greene’s literary work, the intrigue that continues to surround his life, and also to Mewshaw’s ability to tell a captivating story very well.

Be First to Comment