Essayist Shirley Hazzard’s memoir on her friendship with Graham Greene and the expatriate colony on the Italian island of Capri is a substantive and reflective read, in spite of its brevity. It’s a lyrical account of something and someone long vanished, written by an author to whom “it seemed time that a woman should write of Graham Greene.” At the time of publication in 2000, Hazzard’s work was the only major and first-hand biographical account of this prolific twentieth century author written by a woman. But it’s about far more than only Greene. He is the thread that binds together what is ultimately an account of an enigmatic, eccentric and sometimes seedy community of intellectuals, artists and elites from northern Europe, Russia and the United States who had “wintered” and vacationed on Capri for centuries.

Born in 1931, Hazzard was 27 years younger than Greene. By the time they first met in the late sixties, Greene was at the height of his literary fame, while Hazzard had just debuted with her first novel. Her more prolific non-fiction career launched later. Hazzard’s husband — the translator and biographer Francis Steegmuller — was Greene’s age. While Greene on Capri recounts many shared drinks, dinners and outings involving Greene, his companion Yvonne Cloetta, Hazzard and Steegmuller, the closer friendship was between the two men. Part of that has to do with what Hazzard alludes to on a few occasions: a certain prejudice against women that sometimes bubbled to the surface with Greene and was very likely quite common among men of his generation.

The irony, however, was that they had Shirley Hazzard to thank for having built a friendship in the first place. On a December morning in the late sixties, Hazzard was completing a crossword puzzle in Capri’s Gran Caffè when she noticed two Englishmen seeking shelter from the rain. They had just come from Mass at the cathedral and took their seats at the table next to her, where they spoke of the new liturgy introduced at the Second Vatican Council. It was impossible not to eavesdrop. Greene tried to recite a poem from Robert Browning, but couldn’t recall the last line. After finishing her coffee and crossword, Hazzard casually reminded him of it before grabbing her umbrella and leaving. That night, Hazzard and Steegmuller dined at their favourite Caprese restaurant, an unpretentious place called Gemma. Greene and his friend from that morning — the sailor, author and fellow Catholic Michael Richey — appeared there as well. The four shared a table and from that point on, through the seventies and eighties, Greene, Hazzard and Steegmuller would continue their friendship whenever their visits to Capri coincided.

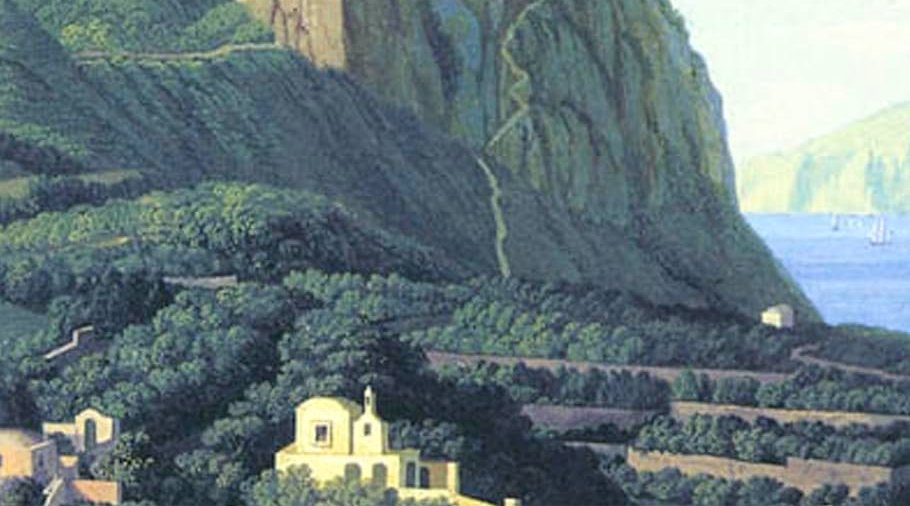

Greene acquired a villa, called the Rosaio, in an isolated corner of Anacapri in 1948. While he lived in Antibes, France, and travelled the world widely and frequently, he would return a couple of times each year — usually for a month at a time — to seek solitude and what Hazzard suggests was a desire for “autonomy” on Capri. He almost never involved himself in the affairs of the island, he didn’t seem interested in the sweeping and dramatic natural beauty of the rugged land, and even when faced with the most breathtaking views that would captivate nearly anyone, he would instead focus his conversations on literature, authors and history. Hazzard notes that Greene wrote a minimum of 350 words per day while on Capri, never taking a holiday from his diligent writing career.

Hazzard’s memoir gives a survey history of the expatriate presence in Capri over the centuries. She estimates that in the early twentieth century, at any given time, the colony of Brits, Germans and Russians, alongside some Swedish royalty, numbered between 100 and 200. This represented the apex of Capri’s appeal among European intellectuals, authors and artists. By the time Greene arrived in 1948, the expatriate colony was waning and by the sixties and seventies, it was a shadow of its former self. As Hazzard notes, one of the remaining mementos of a vanished community are the tombstones of Brits and other northern Europeans in the cemetery.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Greene’s presence was a final reminder of the big personalities that once wintered or sought refuge here. Vladimir Lenin had been among them. Another was Elisabeth Moor, a tough, fiercely independently-minded doctor on Capri who apparently looked like Khrushchev, and about whom Greene edited the book An Impossible Woman: The Memoirs of Dottoressa Moor. As Hazzard writes, Capri seemed to “gather sacred monsters and formidable personalities — Norman Douglas, for instance, or Graham himself — who are ultimately drawn into its fabled strangeness, making part of the myth. ‘Grande personaggio,’ an Anacaprese remarked to me the other day, on the path near Graham’s gate.” The writer Norman Douglas, who died four years after Greene bought his villa in Anacapri, was indeed a larger-than-life, hedonistic, amoral and highly sociable presence in the expatriate community. He was also a wholly unrepentant serial sexual predator. Hazzard makes a passing reference to this. Soon after his suicide in 1952, reports of his abominable conduct, not much of a secret in his circles, overshadowed and negated the merit of his previously celebrated writing.

Hazzard’s memoir is based less on conclusions drawn from personal anecdotes and more on those that she can extract by reflecting on Greene’s life and on the literary, philosophical, and geographic spaces he inhabited. Her memories of Greene are weaved into the commentary on his literary works and fictional characters, on those of his contemporaries and of the artistic traditions of the western world, as well as her impressions of Capri. It’s a multidisciplinary, eclectic work encompassing elements of literary criticism, history, philosophy, travel log and biography. She tries to genuinely understand Greene against the backdrop of his world. In doing so, she offers this:

…there was scarcely a literate person in the English-reading world who had grown up without some consciousness of Graham Greene–of his unquiet, unappeasable spirit and his ability to put clear words to the world’s malaise. Almost to the end, he had kept pace with his convulsed century, detached but not dispassionate; aiming for the heart.

For all that has been written of Greene as a cantankerous, mercurial man — and Hazzard shares episodes about his propensity to spark entirely unpleasant conflicts at otherwise pleasant social gatherings — he certainly had a heart. But as Hazzard adeptly explains, Greene wasn’t likely to display solidarity with entire classes or groups of disadvantaged, marginalized peoples as such — even though he tended to side with the underdog. Instead, he gravitated to the profoundly suffering individual, and even more so if that suffering individual’s experience was in some way singular.

We also learn of Greene’s quiet generosity. Relatively little is written about this, precisely because he performed his good deeds in secret. The most striking example included in this book is how Greene financially supported fledgling author Muriel Spark, when she faced desperate times. Hazzard was friends with both Greene and Spark. In one conversation with Greene, he expressed admiration for Spark’s work, but said that he did not know her. Hazzard then shares in her memoir what Greene kept quiet: “He did not say that — as I knew from Muriel — he had regularly and privately sent money to help her survive her lean first years of writing fiction, the cheques arriving each month with, in Muriel’s words, ‘a few bottles of red wine to take the edge off cold charity.'”

In several episodes, we read of Greene’s capacity for honest self-reflection and to seek forgiveness — such as on one occasion when his temper took possession of his good judgment, leading him to write a letter of apology to Hazzard and her husband. But a more interesting example is when in 1981, as he was about to receive the Jerusalem Prize, Greene faced accusations of antisemitism in one of his early works, The Confidential Agent, published in 1939. He told Hazzard and Steegmuller that he re-read the book and determined: “Yes, there is anti-Semitism in it. I don’t believe I was anti-Semitic. I don’t find it in myself or in my past. But the thing was in the air, between the wars, an infection. Of course it would have been better not to fall for it at all. Many people didn’t.” Hazzard, as she often does in this book, skilfully connects Greene’s words to one of his fictional characters, this time from the novel The Comedians: “It was as though somebody I hated spoke from my mouth before I could silence him.”

An element of loss runs through Greene on Capri. Hazzard’s husband died a couple of years after Greene and sympathetic characters of the day, like the illustrious Harold Acton — residing in Florence, but a visitor to Capri — were gone too. And so much of the book is an ode to a rustic island off the coast of Naples that had disappeared too, through radical transformation in the last decades of the twentieth century. The greatest strength of the memoir, however, is the author’s keen capacity to observe and interpret people and places — remarkably well-read people with a vastness of knowledge that I think puts most of us to shame today, and places marked deeply by both those passing through and those who never left.

Be First to Comment