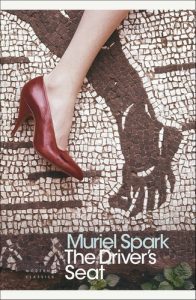

Muriel Spark’s dark and casually brutal 1970 novel, The Driver’s Seat, throws the reader off balance. The boundary between victim and perpetrator is all but erased. Everyone seems distorted — as though we’re seeing the world through a funhouse mirror. Lise, a 34 year old multilingual office worker at an accounting firm in northern Europe, embarks on a solo vacation in the south. She is neurotic, delusional, frantic, silly, a pathological liar and is hellbent on executing an awful, self-destructive plan. At times, she comes across as childishly naive, fragile and vulnerable. In other moments, she’s scheming, stubborn and determined to get her way. Who’s in the driver’s seat in this story — Lise or one of the unsavoury characters with whom she crosses paths?

Lise is perhaps too young to have a classic midlife crisis, but that’s how her behaviour and holiday in an unnamed Mediterranean city feel like. At minimum, she’s bored stiff of the stability and predictability in her life. She’s spent sixteen years working for the same accounting firm, she’s single and she desires a thrill. It also becomes quite clear early on that she’s erratic and mentally unstable. As if to break through a grey, dull existence in the most visible way possible, she buys a gaudy, outlandishly coloured and patterned outfit for her trip — one that will make her stand out wherever she goes. Lise is lonely and she wants to be seen. Yet on a heady day in the Mediterranean, she’s a whirlwind spinning on the peripheries of everyday life, isolated from most people or simply repelling them.

This short novel follows one day in the life of Lise whilst on holiday. She claims not to be interested in sex as such, but the entire purpose of jetting off to a Mediterranean city is to find a man who is “her type.” It seems euphemistic to say that she seeks adventure when what she’s looking for is so macabre and destructive. We’re told early on in the novel that things will end terribly and we’re reminded of the tragedy to come numerous times. Those reminders are almost clinical in their cold, factual tone. There’s an inherent emotional detachment present in Spark’s novels, especially when dreadful things are about to happen to her characters. In The Driver’s Seat, the suspense is found less in discovering what will happen, but rather how it will occur, and who will be involved.

One of the characteristics of several Spark novels is the closed world in which the characters interact and in which the tight plot unfolds. The first part of the book is set in an airplane, as Lise flies to her Mediterranean holiday destination. She sits between two men. One becomes viscerally fearful of her. It isn’t initially clear why he is so uneasy. As his anxiety grows, he asks to be offered a seat elsewhere in the cabin. Meanwhile the other man takes what is clearly an unhealthy, domineering interest in Lise. His name is Bill and he’s a so-called “Enlightenment Leader” in a cult. He promotes “cleansing diets” and a “macrobiotic” lifestyle, and he plans to recruit youth in Naples to join what he calls the Yin-Yang Young. He explains to Lise, who he had just met minutes before, that “on this diet the Regional Master for Northern Europe recommends one orgasm a day. At least. In the Mediterranean countries we are still researching that aspect.” This is when, with so few words and no backstory, we learn that Bill is a predator.

Later in the novel, Spark uses a few more words — but never too many — to paint a very vivid picture of both the place and the person. We read: “The chandeliers of the Metropole, dispensing a vivid glow upon the just and unjust alike, disclose Bill the macrobiotic seated gloomily by a table near the entrance. He jumps up when Lise enters and falls upon her with a delight that impresses the whole lobby, and in such haste that a plastic bag that he is clutching, insufficiently sealed, emits a small trail of wild rice in his progress towards her.” There’s something decidedly sinister about Bill and while Spark communicates this to her reader, she sometimes uses deceivingly lighthearted language to do so. But there’s no mistaking that Bill is creepy, especially when he tells Lise: “I was nearly giving up on you. I was just about to go out and look for another girl. I’m queer for girls. It has to be a girl.”

There are plenty of twists in this brief narrative, so one shouldn’t get too comfortable in thinking that everything has been figured out. So much remains unspoken that the reader often has to rely on instincts and what one feels about the story, rather than much concrete information. In a strange way, The Driver’s Seat is a cross between a police report and a fable. But tying everything together is this theme of control and order, all set against a period of disorder and change in the sixties and seventies. Spark turns that discussion too on its head and her vehicle for doing so is the elderly Mrs. Fiedke, the mostly amicable Jehovah’s Witness and fellow tourist. Mrs. Fiedke shows great patience with the erratic and enigmatic Lise and even a certain maternal concern for her. That said, Mrs. Fiedke is herself a little peculiar. She believes men are, in general, cowards and then has this to say about males:

“They are demanding equal rights with us. That’s why I never vote with the Liberals. Perfume, jewellery, hair down to their shoulders, and I’m not talking about the ones who were born like that. I mean, the ones that can’t help it should be put on an island. It’s the others I’m talking about. There was a time when they would stand up and open the door for you. They would take their hat off. But they want their equality today. All I say is that if God had intended them to be as good as us he wouldn’t have made them different from us to the naked eye…With all due respects to Mr. Fiedke, may he rest in peace, the male sex is getting out of hand. Of course, Mr. Fiedke knew his place as a man, give him his due.”

Everything in this thriller, including an elderly woman’s rant, points to that central question: who’s in the driver’s seat? And while Mrs. Fiedke is first introduced as benevolent and sweet, we soon learn that she’s a bit more complicated than that, as all humans tend to be.

Once Lise arrives to her destination, she spends a dizzying day hopping between various hotels, shopping in a department story for at first seemingly random items, frantically looking for “her type” of man in every corner, getting caught up in a student protest, getting tear gassed by riot police, finding herself face-to-face with a violent car mechanic, stealing a couple of cars — and much more. The sociopolitical upheaval of 1968 frames this novel. While the world seems to be spinning out of control, Lise’s way of exercising ultimate control over her own fate is to choose to place her life in someone else’s hands and then entrusting him to do what she says with it. Spark writes with precision, a sharp edge and quite mercilessly.

[…] Only God is in control. We see this same theme of control, and the desire for it, in novels like The Driver’s Seat and in Memento Mori. And it’s at the heart of this funny, savage story too — which also […]