I have just returned from nearly three weeks in Budapest, Hungary. My time there was a balancing act of family visits, spending time with friends and exploring the layers of history and memory in this region. One of my visits was to Budapest’s Cave Church, or in Hungarian Sziklatemplom. Located in the heart of Gellért Hill, the temperature inside the cave, even in the most sweltering summer heat, stands at a comfortably cool 20 Celsius. Equipped with my camera, this visit to the Cave Church proved the ideal sanctuary from this year’s Europe-wide heatwave.

While the cave itself is ancient and has been tied to Christian history for some time, the Cave Church is rooted in the early twentieth century. Gellért Hill is named after Saint Gerard (or Gellért in Hungarian), an 11th century monk originally from Venice who spent seven years in Hungary tutoring Saint Emeric, son of Saint Stephen I, the first King of Hungary, and then later lived as a hermit in the countryside. He went on to serve as Bishop of Csanád and was tasked by King Stephen with expediting Hungarian society’s conversion to Christianity. Saint Gellért, however, fell victim to a Pagan rebellion in 1046. There are divergent accounts of Saint Gellért’s martyrdom, but the one that every Hungarian child learns about is that he was placed in a barrel (according to some accounts this barrel had spikes) and was rolled down the hill in Buda that now bears his name.

The Cave Church as we know it today dates back to 1924 and was inspired by Lourdes, the Catholic shrine in France. A group of Hungarian pilgrims had been so inspired after a visit to Lourdes that they formed a committee to create a church under St. Gellért Hill, incorporating what used to be known as St. Ivan’s Cave and received enthusiastic support from Gyula Pfeiffer, chief counsel to the Hungarian government. The church was consecrated on Pentecost in 1926.

In tandem, the Pauline Fathers, whose presence in Hungary had been suppressed by Habsburg Emperor Joseph II in 1786, were invited to return after an absence of 150 years, and they did so in 1934. The Cave Church became a centre of Pauline spirituality in Hungary. The order’s return to Hungary, however, was short-lived. In 1950, as part of the persecution of the Church by Hungary’s Stalinist authorities, the Pauline Order was disbanded, the monks deported or imprisoned and the Pauline Superior, Ferenc Vezér, was executed in 1951 after a show trial. He had been falsely convicted of having incited the murder of Soviet soldiers. Fr. Vezér’s remains were buried in an unmarked grave. It was only in 1992, three years after the fall of one party rule in Hungary, that Hungary’s Superior Court posthumously exonerated Fr. Vezér and that researchers located his remains in a corner of Budapest’s Új Köztemető cemetery. Meanwhile, the Paulist Order returned to Hungary in 1989.

When you arrive to the Cave Church, you first find yourself in the Pauline reception centre, which offers information on the Order’s history and audio guides available in multiple languages. From here, a fairly narrow subterranean corridor takes you deeper into the heart of Gellért Hill. The Cave Church is considered a national propitiatory shrine and as such, expressions of faith life are combined with narratives of Hungarian national history.

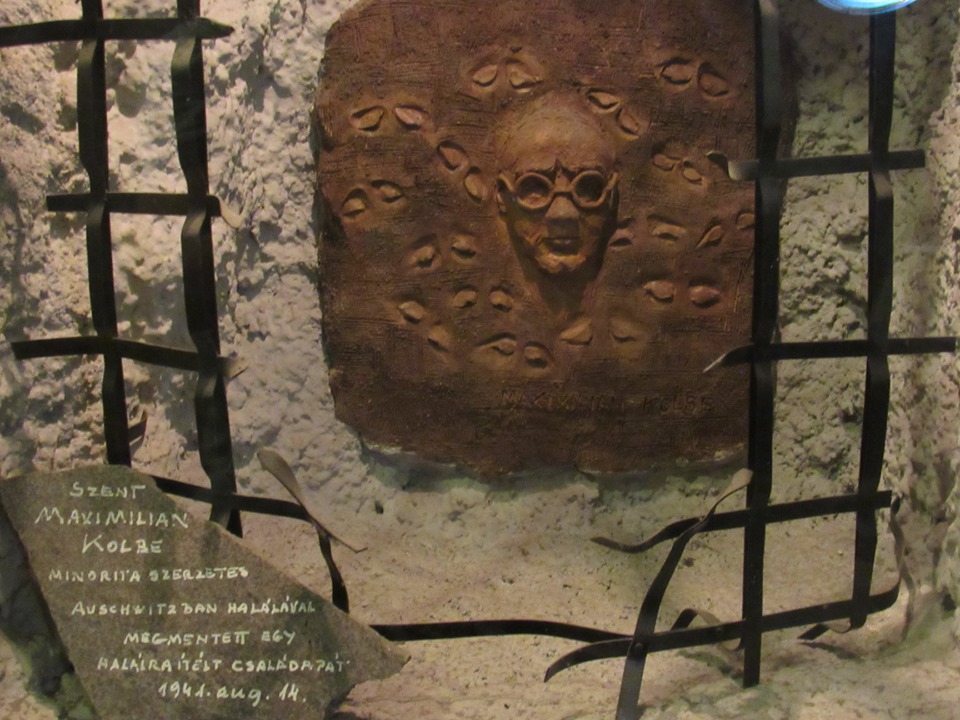

The Cave Church also includes the Sacrament Chapel, as well as the Polish Chapel. It is in the latter that we find the martyred Saint Maximilian Kolbe, a victim of the Auschwitz death camp, commemorated in a particularly powerful way. He endured starvation, but his death resulted in a father’s life being saved so that he could return to his young family. Worth visiting as well, as part of the self-guided tour, is St. Stephen’s Chapel, where examples of ornate Transylvanian carvings, using lime-wood, are displayed.

The Cave Church isn’t among the most frequented tourist sites in Budapest, so it can serve as a space of quiet and cool refuge, in the midst of a bustling and hot summer, for those seeking both a glimpse into Hungarian history and also a space for quiet reflection.

Was it not this Pest hilltop cave that, during the Soviet era, was converted to a youth hostel? I believed I spent several nights there ca. 1972.

Hi Connie,

Fascinating question–I am not sure, and I did not realize that they had a youth hostel there in the seventies. I will look into it.

Thanks for this Chris – I find myself enchanted and drawn to the small church and side chapel that are built into the cave. There is an invitation in it’s simplicity. I found myself wanting to simply sit and be in one of the chairs.

Thanks for your feedback Eleanor! Yes, I also prefer some of the smaller, quieter churches, versus the grand cathedrals that attracts crowds of visitors.