This candid memoir explores how a man who built a successful career in the technology sector as a public relations specialist is forced to confront his repressed childhood memories of abuse from the early 1980’s. In 2002, when faced with the series of investigative reports by The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team detailing the systemic abuse of minors by Catholic clergy, and its cover-up, Emerton began the process of coming to terms with what he experienced at the hands of a predator priest. Only a relatively short portion of this memoir documents the abuse itself; the focus is on exploring how and why victims repress their trauma, how concerned Catholic lay men and women responded to the crisis and how Emerton moved incrementally towards both recognizing and speaking openly about what he suffered.

Emerton’s experience of abuse has much in common with the stories of countless others. I use the term countless deliberately, as it is certain that many victims of clergy abuse buried their trauma in silence and their stories will never surface. As such, it is important to treat any figure that claims to estimate the proportion of Catholic priests who abused minors with great caution. As a 14 year old, young Mike Emerton and his family were parishioners at St. John the Baptist Parish in Haverhill, Massachusetts. Michael’s mother was a former Carmelite and, as he writes, “beyond the pages of the Bible and under the pews there was a mysterious pool from which she drew a deeper understanding of God.” To earn extra money for her family, she worked part-time in the parish, cleaning the rectory and cooking for the priest. During this time, Michael and his siblings played on the church’s grounds. The family had a close relationship with the priests who served this parish and clergy were frequent visitors to their home for dinner. The young Mike, who began wearing a scapular out of a belief that this would help him avoid damnation, and who also served as an altar boy, found comfort in his parish.

Things changed with the appointment of Ronald Paquin as pastor; he was in his thirties–younger than the previous priests. Paquin took a special interest in young Mike Emerton and impressed the boys in his parish by driving a white ’79 Toyota Celica Supra and by riding a motorcycle. Mike was excited to ride the motorcycle with him and Fr. Paquin was happy to drive him around. Fr. Paquin also invited Mike and other teenage boys to his bedroom in the rectory, where he served them beer. As the friendship between Fr. Paquin and Mike became closer, the pastor began asking sexually explicit questions. Mike’s initial reaction was to find these discussions and questions odd and uncomfortable, but then he quickly comforted himself by thinking: “I found solace in the thought that he was a holy man and that he must have some reason for everything. I don’t understand Jesus as he does…”

Fr. Paquin took then fifteen year old Michael on a road trip to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, which involved a gambling cruise and alcohol. The priest also insisted that the teenage boy share a bed with him. At first the confused boy balked at the idea of sharing a bed with the priest. But then he rationalized why it was acceptable after all. He writes: “I looked into his face and he seemed hurt by me not wanting to lie with him. I began to feel guilty. He’s taking me on this trip and paying for it all…He is a caring man of God so, naturally, he may act differently than normal folks.”

Later, Michael along with his older brother Patrick (who edited his memoir), and his brother’s friends all went on a camping trip in Maine with Fr. Paquin. The priest insisted that Michael sleep in his tent and undressed the teenage boy, explaining that it was too hot and he would be more comfortable in his underwear. Michael remembers vividly being molested by the priest. Their relationship ended after this trip and Michael kept a distance. Fr. Paquin, however, moved on to other boys in the parish. This surprised Michael, as he had assumed all along that the priest only did this with him. Fr. Paquin took a group of boys on an overnight trip to Bethlehem, New Hampshire. On the way back, Fr. Paquin, driving while under the influence, crashed the vehicle on the road and one of his young passengers, Jimmy, died in the accident. In a most outrageous turn of events–at least from today’s perspective–Fr. Paquin presided at Jimmy’s funeral and printed his own personal pet name for his victim, “Jim Boy,” on the cover of the memorial booklet.

Michael Emerton gradually distanced himself from the Catholic Church. He buried the guilt and shame deep in his psyche and built a comfortable middle-class life for himself and his wife, and a good career. The Boston Globe’s stories in 2002 on clergy abuse, which led to Fr. Paquin’s arrest, a rape conviction and a sentence of 12 to 15 years in prison, shook up his world and forced him to confront his past. Emerton reached out to a new lay Catholic public advocacy group established in Boston called Voice of the Faithful (VOTF). The grassroots organization aimed to support victims of clergy abuse, partner with priests of integrity in the Catholic Church and also speak out against clericalism, demanding better of the treatment of the laity. At first, Emerton approached VOTF simply as a concerned Catholic looking to help by offering his skills as a PR specialist, rather than as a victim. It was his way to be part of a process of change without confronting his own experiences.

While all major American news networks followed VOTF’s work with acute interest, and as Emerton organized press conferences and coordinated interviews with victims and VOTF members, many bishops and priests in the United States saw any cooperation with the lay-led group as anathema. The demand from much of the Church hierarchy that lay people are to simply “pray, pay and obey” remained intact, even as the scandal unfolded and grew. VOTF, however, took concrete steps to force more accountability and lay leadership in the Church. In the Archdiocese of Boston, VOTF began fundraising for Catholic charities and creating a pool of funds that would not be controlled by Cardinal Bernard Francis Law, an architect of the cover-up of the clergy abuse scandal, and that could not be used by diocesan lawyers to quietly pay off survivors in exchange for their silence–as had been the practice in the past. VOTF, however, had a mission and purpose far beyond the Archdiocese of Boston. A Dallas Morning News investigative report from 2002 discovered that 111 out of 178 Catholic dioceses in the United Stated engaged in the active protection and cover-up of clergy abuse. The day of public reckoning for American bishops also came during a conference in Dallas, where the Church’s leaders at long last began to display the first signs of humility by seeking forgiveness.

Emerton recounts how he eventually came to share with people around him, including his wife Janis, what had happened–that he was one of the many victims of clergy abuse. One of the reasons he hesitated to talk about this twas out of fear that by doing so, his victim status would forever be attached to his name and that he would be the subject of quiet gossip and even crude jokes about pedophile priests. Even after he shares his own story, however, he decides not to focus on the personal, but rather on the prophetic work of groups like VOTF and the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP).

The memoir, while justifiably critical of the systemic failures of the Catholic Church and the cover-up initiated by its leadership–in which Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) were both complicit–also documents the work of priests who displayed integrity. One of these is a Fr. Walter quoted in the memoir as saying: “Don’t let [your priest] live, act and speak as a prince when he should be a shepherd. Call us priests to task. Call us priests to be what we say we are for you.”

More than anything, Emerton’s memoir provides first-hand insight into how Catholic laity responded to the crisis of clergy abuse and systemic cover-up in the Church. It’s more about these lay efforts than about the author’s personal life. Emerton’s memoir is a compelling primary source document that explores how lay people, in the wake of a deep crisis in the Catholic Church, fought to bring accountability to the church and demanded to finally implement the principles of the Second Vatican Council.

________

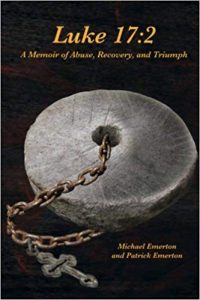

N.B. — About the verse referenced in the title (Luke 17:2), in which Jesus says to his disciples: “It would be better for you if a millstone were hung around your neck and you were thrown into the sea than for you to cause one of these little ones to stumble.” (NRSV) The term “little ones” may be a reference to children or it may in fact be a more universal reference to everyone.

Be First to Comment