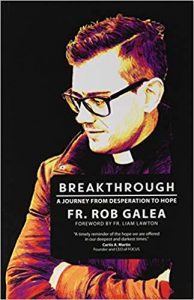

Father Rob Galea, a Maltese Catholic priest serving in Australia, writes in a highly conversational style about his journey from addiction, depression and anger to a life of faith and ministry. Somewhere between memoir, homily and a Catholic youth group talk, the book documents the path of a priest who speaks quite candidly of his own struggles and who is unconventional in his approach to pastoral ministry.

Born in 1981, the young Robert Galea grew up in a comfortable, middle-class home in Malta. He led a privileged and fortunate life, in a loving close-knit family. Fr. Rob recounts a Maltese tradition called Quccija from his first birthday. The infant is presented with a silver tray of items and the one chosen by the child is believed to serve as an indication of the type of career or life he/she will lead as an adult. The items on the silver tray include, among others, a hammer (labour), a calculator (accounting or IT), a rosary (Holy Orders) and an egg (a life lived to the fullest). The young Robert chose the egg.

Robert describes his early childhood as idyllic in this scenic Mediterranean island nation. But as he enters his teenage years, he experiences bullying and later, surrounded by negative influences, he becomes addicted to alcohol, drugs and tobacco. The young Robert begins shoplifting and engages in other forms of theft, he displays depression and anger management problems. He fights with his father and withdraws increasingly into his room.

At age 17, he recounts a type of catharsis moment; through prayer, he develops a connection to Christ and begins to face his addictions and mental health struggles. Fr. Rob’s language is almost identical to that used by “born again” Evangelical Christians. Where he does stray from this narrative is the emphasis he places on community and on a communal, rather than a completely private approach to faith. It’s his involvement in Catholic youth groups, his music (guitar and singing) and daily participation at Mass that helps Robert move in the direction of a healthier mental space. To his credit, however, he makes several mentions of the importance of seeking professional medical help as well.

The discussion in the book around the decision to join the priesthood is sincere and raw. It’s also a little jejune. Robert looks around him and finds that priests tend to be “old men in their black shirts and white collars who never smiled.” But then Robert meets Fr. Giovanni Sacca who is the polar opposite: “I was taken by how young Padre Giovanni was. I couldn’t even believe he was a priest! He was, without a doubt, the coolest, hippest priest I have ever seen.” A close friendship develops between Robert and Padre Giovanni. The book also includes a cursory discussion of the challenge of celibacy and a more fulsome exploration of the concept of “death to self.” A moment of deep honesty, however, is how Robert documents his father’s reaction to the news that he is joining the priesthood. His father thinks that his son is becoming a religious fanatic, that this is a fleeting phase, and is disappointed that he would not carry on the family business.

The exploration of life in seminary is insightful. On the one hand, seminarians are very human and have diverse liturgical preferences. In one case, a heated argument leads to a seminarian throwing a pencil at Robert’s head. The seminarians also play practical jokes on each other. They behave like young men in a university residence. Sometimes seminarians leave, having discerned that the priesthood is not for them. In one instance, Robert was so upset at the departure of a seminarian that he cried for days. On the other hand there is an implicit sense, one that the author probably did not intend to convey, that these men are becoming somewhat inward-looking and separate from the rest of society and church. The author feels that seminary is a thorough education which prepares priests to be highly multifaceted. Fr. Rob writes:

A priest often serves as a counsellor and spiritual advisor. We are there for people at the worst and best moments of their lives…A priest is an evangelist and a teacher of faith, a conflict resolver, and has to know how to be a good and just employer. We administer sacraments, defend the faith and help build people to become all that God has called them to be. We study philosophy, theology, anthropology, sociology, and psychology, as well as canon law and business administration…The studies we undertake are designed to help us understand how people think, how they act in society, and how they understand and reach out to God…As someone who values work in the community, it’s vital that I have a powerful understanding of how people work. We provide more than just religious instruction–we are also community service workers.

While there is a thin, but important professional boundary to be maintained between a counsellor and a priest, what Fr. Rob describes above is perhaps the ideal scenario of what a seminarian is formed to become. Looking at many young men leaving seminary today and entering active ministry, does Fr. Rob’s description match reality? Are these men indeed well-rounded, motivated by compassion and a sense of pastoral mission, and emotionally well-adjusted?

Robert is ordained a Catholic priest in 2010 and his life path, at least for a member of the clergy, is atypical. Thanks to his talent as a musician, he participates in X Factor, although eventually finds that this isn’t the best fit for a life dedicated to pastoral work. He also maintains an active social media presence and continues to travel for talks and concerts, while serving as an assistant pastor at St. Brendan’s Shepparton, in the Diocese of Sandhurst, Australia. His ministry focuses on youth and the marginalized, especially juvenile offenders and those who have been involved in prostitution. His message does come from a point of compassion, especially when he writes: “God whispers, and then it is up to us to listen and respond or to turn away. God will not love us any less if we do, and in His love and mercy, He will help us find joy in an alternative life path.”

I think that Fr. Rob’s book may speak most to a niche readership, namely Catholic youth and young adults already involved in parish life or at least from Catholic families. He includes QR codes throughout the book, leading his readers to additional online content, including to his music. This may appeal to some young audiences, but perhaps I am too old, as I found it distracting and even a little gimmicky. Some books, whether fiction or non-fiction, that arise from a fountain of Catholic faith have a broader appeal, including to non-Catholics and those of no particular religious faith. This is due to the manner in which the author engages and grapples with doubt, a level of critical self-reflection and their nuanced approach to the Church and its place in society. Fr. Rob’s language and narrative, though stemming from a place of love, is based on an emotionally-charged, emotively expressive and enthusiastic faith, leaving little space for subtlety. This type of language and story may “rally” people already engaged actively in the Church, especially in Charismatic Catholic circles, but I am not certain that it speaks to those closer to the margins of faith or indeed on the outside. As a reader coming from a Catholic background, but comfortable with doubt, my preference is for a “quieter,” more introspective and more complicated exploration of faith and church.

Fr. Rob could add dimension to his story by being more descriptive of his struggles and how he worked to overcome them, and perhaps how these experiences helped in his outreach to the marginalized. This would involve providing more examples of how addiction manifested itself. His candour in sharing the fact that he struggled with addiction in various forms (alcohol, drugs, tobacco and pornography) is admirable, but as an author he could go one step further: he might describe what this meant, so that his message truly engages our mind and imagination.

Be First to Comment