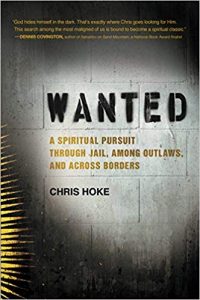

This book isn’t about a pastor’s triumphant journey into jail to teach inmates and preach about salvation. Rather, it’s an exploration of how a wavering, vulnerable man, sometimes without convincing answers, a clumsiness and awkwardness that comes from raw uncertainty, opens himself up to learning from the gang members, felons and violent schizophrenics to whom he ministers — men whose worst sins are on full display and who have inhabited some of the darkest quarters. In some ways, reading Chris Hoke’s book Wanted — A Spiritual Pursuit Through Jail, Among Outlaws and Across Borders, is like watching Henri Nouwen’s concept of the Wounded Healer come to life in the early years of the twenty-first century.

A quote from Trappist monk Francis Kline forms the foundations of Hoke’s book. Kline wrote: “Only in the darkness are certain, more choice intuitions of God received.” In practice, Hoke is a night owl — his visits to county jails, to hold bible studies and to meet one-on-one with inmates, often take place at night. When the material world is most tuned out, either before dawn or after dusk, our senses come alive, circumventing the static that rules the daytime, so as to connect us with the transcendental. Hoke draws on the long traditions of contemplative prayer and meditation, writing about “entering the silence of the mind like a lake before dawn, its surface still undisturbed by the day to come.”

The darkness and silence are present in every chapter of Hoke’s book, as characters weave in and out of the author’s journeys through the correctional system and in his work with undocumented migrant workers. Hoke himself inhabited the darkness of depression and drift before he unexpectedly and with little formal training became a jail chaplain, finding himself having to ‘wing it’ during bible studies and one-on-one visits with felons in Washington state. Hoke sought to understand Scripture through his interactions with incarcerated felons or those out on parole. The more he interacted with them, the more it dawned on him how strikingly similar the many troubled characters in the Bible, including some of the greatest prophets of Hebrew Scripture, were to the convicts in the jail cells of Skagit County, Washington. Hoke writes: “The cross hanging behind most preachers haunted me. The first-century electric chair. Cosmic redemption happened in the seat of criminality, out on the edge of town, between two dying thieves — and when the land had grown curiously dark.”

The characters in Scripture revealed themselves to have much in common with the troubled people inhabiting Washington’s jails and prisons, and those drifting on the neglected edges of society. Hoke realized that the narratives in the Bible could speak to these men in a unique way. Felons, gang members, people with the most troubled pasts could relate to what they read, because in people like Jeremiah, Abraham and Moses they often saw a compelling reflection of themselves. What all of this meant for Chaplain Chris is that by ministering to inmates, the pages of Scripture came to life and this helped him grow in his own spiritual understanding.

Sometimes Hoke’s ministry does not go according to plan. In one chapter, we get a glimpse into a bible study gone wrong. One of Hoke’s regulars convinces nearly all the men in his dorm to attend — mostly through various forms of coercion. Hoke is sort of grateful for the gesture, which was meant to please him, but also concerned about the coercion aspect. The bible study, however, becomes a disaster. The group reads a parable from Matthew on the wedding banquet and Hoke’s enthusiastic inmate assistant is animated, getting other inmates to help act it out and really consider the message. Jesus’ parable is about a king who prepares a great wedding banquet for his son and gets his servants to invite the community, respectable society only. Yet people show little interest in coming. The king then instructs his servants to invite anyone from the streets, including “the bad ones.” The banquet bustles with all these people who lived on the margins, but who the king had invited for a marvelous feast; a perfect narrative for a prison environment. Hoke wants to end the parable there, but his inmate friend persists that they continue to read the rest of the story. It continues like this:

“But when the king came in to see the guests, he noticed a man there who was not wearing wedding clothes. He asked, ‘How did you get in here without wedding clothes, friend?’ The man was speechless. “Then the king told the attendants, ‘Tie him hand and foot, and throw him outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ “For many are invited, but few are chosen.”

Hoke’s inmate friend is hurt, furious and disappointed. “What the fuck, Chris? What do you expect from people like us? We don’t have all the right clothes. We never look right. You should know that!” — the inmate friend roars. Hoke tries to explain that in Palestine, it was customary for the host to provide wedding guests with an outfit to wear. Was this man off the streets simply refusing to wear the clothing provided to him, thus disrespecting the host? The explanation seems forced. Hoke then offers a different interpretation: what if the person who would not put on the robes was one of the “good” people, who was unhappy that all the “bad ones” had been invited–and he did not want to be dressed like them or be identified with them? Why do those who read this passage automatically presume that the guest who refuses to wear the robe is one of the “bad ones,” rather than one of the “respected” members of society? It’s plausible as an interpretation, but Hoke’s inmate friend isn’t entirely convinced. There is an endearing honesty to how Hoke shares his ministry, including his failures, with his readers.

In another chapter, we meet inmate Michael Jenkins, who has a tattoo on the side of neck that reads “Fuck the world.” At this time, Hoke was working with another chaplain, someone called Bob who had been a mentor to him in this ministry. They are sitting in bible study when Bob can’t keep his eyes off the words tattooed on Michael’s neck. The inmate becomes self-conscious of the staring, but then Bob says: “I’m just looking at your tattoo here and thinking, That’s something Jesus’ disciples might have said.” Moments later Bob asks Michael what he means by the term the world. Initially, Michael hesitates, as he tried to formulate his thoughts. Then he offers: “The system, you know — the courts, the laws, prisons, cops, society…Just the way the world works, you know?”

Later, Hoke tries to reconcile this world with the one in John 3:16, where we read about how God so loved the world. In a bible study with homeless youth in Seattle, Hoke looks for an answer from those who come from the streets. One of them gives the following response to the world that was so loved: “That’s what God created. That’s what we love too.” The created world, the natural world, is to be loved — it isn’t hateful. Are we then to hate the people who inhabit this world? Another homeless teenager offers, in relation to verses like 1 John 2:15, where we are told not to love the world: “It’s not talking about people, saying we shouldn’t love people. We’re people. I don’t think Jesus was saying he was hated by a few specific people. It’s something else. Something bigger.” The something bigger is a type of system that takes people who have it within them to offer their best and yet sees them project their worst. Building on a definition of “the world” offered by another former gang leader, Hoke writes: “The world makes humans into something less than they are.”

Broken childhoods, abuse, addiction, poverty, marginalization and mental illness are the recurring factors that serve as a backdrop to the crimes, often horrific, committed by the men in this book. Hoke does not use these factors to explain away the crimes committed, nor to lessen the tragedy experienced by victims — and ultimately by the perpetrators too. Hoke does not appear to be driven by naïveté. One of the people we meet is called Connor Harrison — a young man from a loving family, the son of parents who tried their best to understand and cope with his paranoid schizophrenia. His parents, Debbie and Bill, were warned that Connor could become violent, but as Hoke recounts, they decided to take care of him at home, “making themselves vulnerable to his illness.” Connor began to see his father, a middle-aged high school music teacher, as an enemy of cosmic proportions. A voice inside his head told him that he must show “courage” and kill his father, who represented power, in order to save the weak. One night Connor murdered his father. Hoke first visits him in jail and then in a state asylum, and he spends time with his grieving mother too — who had lost both her son and husband.

Through his visits with Connor, Hoke explores mental illness, specifically the idea of hearing voices. He takes a different approach than the dichotomy that we sometimes see between a strictly scientific understanding of pathology and one that focuses mostly on the spiritual — such as demonic possession. How many of the characters in Scripture displayed signs of what we could today label as mental illness? Where is the boundary between mental illness, as understood in a secular sense, and religiosity? Do people with mental illness somehow have an amplified connection to the transcendental? These are some questions Hoke explores, and they are fair questions, given what we read in the Bible. Hoke explains:

“I’d been studying the Hebrew prophets. They heard more than clear, verbal oracles from the Lord. Rather, they shuddered with terrors and torment, often appearing quite unstable, maybe bipolar, swinging from jubilant praises of God to rage and even suicidal despair, all right there in our Bible’s thin pages. The prophet Jeremiah, for example, looked much like the homeless youth I’ve met: a teen making a nuisance in the city streets and locked up repeatedly by authorities…Ezekiel did strange things like make demonstrations with feces in the street and lie comatose for days while receiving revelations. The Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel spent much of his life studying these figures. Heschel describes the prophets not so much as official spokesmen with verbatim divine pronouncements, but as humans with a severe ‘sensitivity to evil.’ To the prophets, he writes, ‘even a minor injustice assumes cosmic proportions,’ and the prophet’s ‘ear is attuned to a cry imperceptible to others.’ They are so sensitive to what we overlook or have ceased to feel, they appear insane…The question of religion in the Bible, he says, is not so much about humans seeking God, but God seeking us. Maybe some people can actually feel that, and can’t shake it.”

In one of Hoke’s visits with Connor, he notes that Abraham heard one voice, allegedly a divine one, telling him to kill his firstborn son Isaac as a sacrifice and as proof of his faith. But then another divine voice tells Abraham to stop this violent act. Hoke rejects the popular interpretation of this verse, which claims that God tested Abraham’s faith, deliberately pushing him to the edge, only to pull him back by saying that it was really just a (vicious) test and that He wasn’t serious about sacrificing Isaac. Hoke offers: “So maybe…Abraham was not being tested by one God but was caught before two opposing and very real voices. One saved him from following the bloody orders of the other. Abraham could have been the patron saint of schizophrenics.”

Hoke explores the concept of listening and hearing, but also of discerning. He paraphrases Mother Teresa, who said that prayer was about listening. When she was asked what God would say to her during prayer, she responded that He said nothing — God just listened. In a world with so much noise and so many voices, often conflicting, Hoke writes about the power of two people sitting in a room in silence — communicating without a word being uttered and doing so by being attentive to the stillness. That idea doesn’t come from Hoke. It arises from his visits and interaction with Connor.

Although Hoke’s book offers a critique of the correctional system in the United States, as well as of the media’s portrayal of those who commit crime, most of this is done implicitly. Wanted is not a journalistic opinion piece on the failures of the justice system; it is far too introspective for that. Through narration driven by humility, and drawing on Catholic mysticism, as well as Pentecostal and Jewish insights, Hoke suggests that the people we may think are the worst, because they have done the worst, have unique insight into Scripture, the transcendental and into the human condition. Hoke goes behind bars, into this darkness, first and foremost to listen. Through this listening and his gentle, authentic presence, he grows personally and also learns to serve those who are most neglected.

Be First to Comment