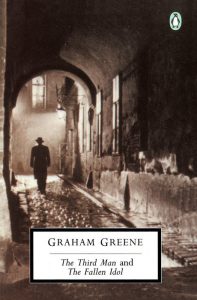

Iconic twentieth century author Graham Greene referred to some of his works somewhat unfairly as “entertainments,” and among these are The Third Man and The Fallen Idol — two novellas published as one volume by Penguin. The Third Man is, in some ways, an archetypal mid-century detective mystery and The Fallen Idol is a psychological thriller. But Greene takes such care in establishing atmosphere and in developing key characters in these short works — primarily through a command of language that is evocative, yet economical — that it isn’t accurate nor just for us to think of either work as ones that we might today pick up from the bin, read solely for the purpose of quick amusement and then toss.

Although entirely separate narratives, there is a common element that runs through both The Third Man, the longer of the two pieces, and The Fallen Idol. In both stories, we have a character who is admired by a naive protagonist to the point of becoming initially blinded to his darker, shadow side. In each story, the protagonist is used and abused by the man on the pedestal. In The Third Man, it is a young English writer called Rollo Martins, the author of tacky throw-away paperbacks published under a pseudonym, who is dragged into the seedy criminal underworld of war ravaged, Allied-occupied Vienna by his friend Harry Lime. It turns out that Lime is involved in a deadly penicillin racket, and is largely unmoved by the tragic consequences of his crime. For the longest time, Martins refuses to believe that his friend, seemingly the victim of a violent conspiracy, could possibly have as unsavoury a character and an even darker past as the authorities of occupied Vienna suggest.

In The Fallen Idol, we meet wide-eyed and innocent Philip, a seven year old boy from an affluent English family, who finds himself in the care of the home’s butler, Baines, and Mrs. Baines, while his parents are away on a two-week vacation. Little Master Philip seeks and enjoys Baines’ attention, but he flees the severe and hard-hearted demeanour of Mrs. Baines. When the boy discovers that Baines has developed a close friendship with another woman, but doesn’t understand what the two adults are really up to, he is asked to keep it a secret from Mrs. Baines — who becomes suspicious and also tries to convince and bribe the little boy to side with her and to “out” her husband as an adulterer. Philip is caught unwittingly in a cycle that moves from psychological to physical violence, and he is scarred by the experience.

Both The Fallen Idol and the The Third Man became films, in 1948 and 1949 respectively. On both, Greene collaborated closely with film director and producer Carol Reed. Greene had originally entitled The Fallen Idol as “The Basement Room,” and had written the piece in 1935 while en route home to Britain on a cargo steamer from Liberia. In contrast, The Third Man was conceived as a motion picture from the start. In the preface of the Penguin edition, Greene offers insight into his relationship with Reed, and how as an author he collaborated with a filmmaker to transform a story for the silver screen. On turning The Third Man into a film, Greene shares:

“Carol Reed and I worked closely together, covering so many feet of carpet each day, acting scenes at each other. No third ever joined our conferences; so much value lies in the clear cut-and-thrust argument between two people…The reader will notice many differences between the story and film, and he should not imagine these changes were forced on an unwilling author: as likely as not, they were suggested by the author. The film in fact is better than the story because it is in this case the finished state of the story.” Greene praised Reed as having “that particular warmth of human sympathy” and the “power of sympathising with an author’s worries and an ability to guide him.”

The Third Man, with its plethora of characters and the unusual vantage point and narration by policeman Colonel Calloway, who gets into the head of the protagonist and presents his voice to an extent that normally would not be possible for someone learning about another person and his past purely through discussions and interrogations, requires careful concentration from the reader. In contrast, The Fallen Idol is a much more straightforward story, owing not only to its short length, but also to the small handful of characters and the fact that we are seeing everything through the eyes of an innocent and simple child. It’s hard for the reader not to care for poor Master Philip — we understand what he does not in everything that is happening around him, and we know the trauma that he will carry from having been caught in the middle of adult deception and violence.

Be First to Comment