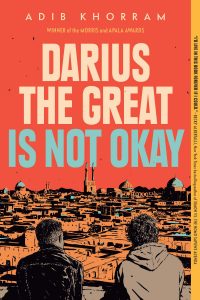

In this coming-of-age story, Adib Khorram provides the sort of dimension to Persian culture and to Iran as a country that one is unlikely to find in much of the media. And while offering vignettes on Persian customs, cuisine, the Farsi language, landmarks and the demography of Iran, the novel’s overarching theme is that of mental illness.

The protagonist, sixteen year-old Darius Kellner, isn’t especially endearing in the first chapters of the book. Initially set in Oregon, Darius –an awkward and uncertain teenager — is half Star Trek nerd, half tea snob. It’s a curious combination. He works part-time at a shopping mall tea shop that sells artificially flavoured teas bearing silly, thoughtless names — like Blueberry Bliss. Tea Haven engages in what a more serious tea drinker would likely consider to be the commercialised bastardisation of the ancient custom and art of tea-drinking. That’s certainly what Darius seems to think, and he aspires to find gainful employment at Rose City Teas — a hipster joint for the sort of people that Mr. Apatan, the owner of Tea Haven, labels elitist. Mr. Apatan says what this reader thought, especially seeing how Darius accuses everyone he doesn’t fancy as being pedestrian. He applies the term “Soulless Minions of Orthodoxy” incessantly.

In the first chapters, when Darius isn’t lost in the world of Star Trek verbiage, he’s either preparing tea for himself or preoccupied with how his father is a “Teutonic Übermensch.” One would think that Darius’ father, Stephen Kellner, is a Nazi terror. Yet he genuinely isn’t that at all. It’s Darius’ own failing sense of self-worth that leads him to believe that he could never reach his father’s high standards — his stoicism, his self-discipline and his perfectionism. Darius also believes that he is damned to be a disappointment. Darius has longish hair, he doesn’t excel in sports nor in areas of traditional interest to boys, he doesn’t stand up for himself when teased or bullied at school and he struggles with his weight. To varying degrees, Stephen Keller does take issue with each of these things. But as much as Darius loves his Persian immigrant mother and demonstrates a deep care for his feisty little sister Laleh, he treats his father unfairly. The one moment of grace and genuine bonding with his father is when he watches Star Trek episodes with him. Yet Darius and his father have something significant in common: they are both medicated to manage their clinical depression.

Darius also struggles with his identity and sense of belonging. He’s half-Persian (or, as he puts it, a fractional Persian) and unlike his little sister, he hasn’t mastered Farsi. He feels like he doesn’t belong anywhere. But the opportunity to immerse himself in his Persian roots comes when his grandfather in Iran nears the end of his life due to an inoperable brain tumour. The family of four take the long journey to Tehran and then a further car ride to the grandparents’ family home in the city of Yazd. All of a sudden, Darius — now called Darioush by everyone in Iran — finds himself in the midst of a loving, extended Persian family. He also sparks a close friendship with a neighbourhood boy called Sohrab. They play soccer and spend long hours sitting on the roof of a public washroom taking in Yazd’s mostly beige skyline — punctured by the sight of minarets, the domes of mosques and the sounds of the calls to prayer. Throughout the novel, Darioush’s relationship with Sohrab is a platonic one — yet it’s clear that he is struggling with his sexuality, but doesn’t have the words and courage to express what he is really feeling.

Khorram’s novel comes alive once the Kellner family lands in Iran. It isn’t just the colourful descriptions of the food and customs — especially the mind-boggling civil practice of Taarof (a social dance where the recipient of a gift or favour first politely declines the help from the giver)–but most of all the diversity of Iran that comes across very effectively. Darioush’s family is Zoroastrian, while Sohrab follows the Baha’i faith. The image of Iran as a monolithic Islamic society is — thankfully — challenged in this novel. Some of the descriptions of Zoroastrian practices, such as sky burials and the Tower of Silence, are wonderful tools to expose western readers, especially the young adult audience, to faiths and practices, and an image of Iran, that would be entirely foreign to most.

Khorram doesn’t offer a sanitised view of Iran. Sohrab’s father is a political prisoner, Darioush has a run-in with a customs officer at the Tehran airport, it’s clear that minorities face persecution and there is a real lack of understanding around mental illness, particularly clinical depression and the chemical imbalance that gives rise to it.

While Darius the Great Is Not Okay has many valuable qualities, there are persistent copy-editing issues that I find surprising given that this novel was published by one of the “Big Five” publishers. The most significant of these is the eyebrow-raising repetition of certain words and terms. The word “squinted,” when describing Sohrab’s smile is repeated well over two dozen times in the novel — sometimes page after page. Similarly, “Soulless Minions of Orthodoxy,” “Übermensch,” and “Teutonic” keep appearing so often that it’s distracting. All of this weakens the dialogue and the overall narration. It also means that not infrequently, the story’s author is “telling,” rather than “showing.” It seems as though the author is trying to recreate teenage social awkwardness and habits by using “um” frequently in dialogue. I see what the author is doing, but I don’t think these habits of speech translate well in written dialogue. To emphasise the tension between Darioush and his father, and the sense of alienation, Dad is frequently referred to by his full name throughout the novel, namely Stephen Kellner. Again, I see what the author is trying to achieve, but it’s awkward. It would have been better to show, in different ways, that detachment, estrangement or alienation.

This novel grew on me as I progressed through it — as did the protagonist. It got me thinking about the perceptions of the “home country” within diaspora communities and that first look at the ancestral land when a member of the diaspora gets to go “home” for the very first time or after many decades away. That’s an experience that so many of us across different cultures share.

Be First to Comment