Robert served 12 years of a 20-year prison sentence for his involvement in the Irish Republic Army (IRA), and in the bombing of Belfast City Centre. Mark served as a British military officer during the Troubles. Today Robert is a prominent community leader in the Catholic Falls Road area of Belfast, as well as a Sinn Féin party activist. Mark is a community development officer on the opposite side of the Peace Wall, in the Protestant Shankill Road neighbourhood. What brings the two men together for the briefest moment is that they provide opposing perspectives as part of a political walking tour called Conflicting Stories. Both speak the language of reconciliation and Robert even wears a pin produced by the European Union announcing as much.

This summer, I met Robert in front of the grim Divis Tower, the 20-storey community housing apartment building that is an enduring symbol of The Troubles in Belfast. From 1970 until 2005, the top two floors of the tower were reserved for the British armed forces. Perched on high, they were able to monitor the community that had been plagued by sectarian violence since 1969. And British snipers were themselves the source of violence. It was only relatively recently, in 2009, that the top floors of the tower were converted back into apartments.

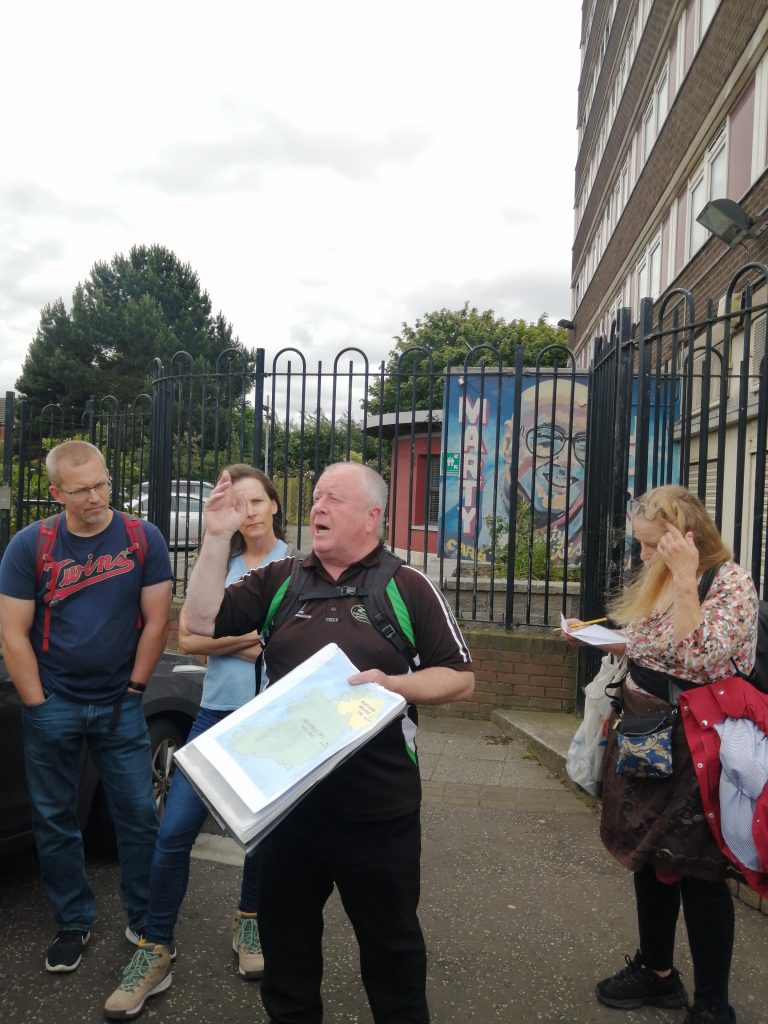

There were ten of us in the tour group. After brief introductions, Robert jumped right into his story. As much as this wasn’t a polished tour, it was authentic and personal. As we made our way along Falls Road, Robert reminded us that the 42-feet Peace Wall was never far away — it lurked behind buildings, curving its way around the neighbourhood like a serpent. Initially, Robert explained, Catholics in the Falls Road area didn’t have weapons — they were at a disadvantage. Yet the Civil Rights movement in the United States inspired them to launch their own movement for rights in Northern Ireland. When police shot at the St. Comgall’s Catholic School on Falls Road, they were at a loss to defend themselves. Robert became involved in bomb-making, and he was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment in 1976. He was just 18 years old at the time.

Robert engaged in various forms of disobedience whilst in prison — often with severe consequences. He served time in what was known as H-Block 4, part of a prison complex south of Belfast that housed political prisoners. The complex became a symbol of repression during The Troubles, was shuttered after the Good Friday Agreement and demolished in 2006. While imprisoned, Robert refused to wear a prison uniform. As punishment, he was kept in solitary confinement nearly 24 hours per day — without clothing and without so much as a blanket. He spent four years in solitary and during this time was only allowed to leave his cell to shower. Out of protest — and perhaps also as a result of a decline in mental health that anyone in these conditions would likely experience — he stopped showering in March 1978 and only resumed bathing three year later, in March 1981. In that same year, 10 prisoners died while on hunger strike in this prison complex. Bobby Sands became the leader and icon of this resistance.

Murals along Falls Road didn’t only feature people like Sands; they connected the symbols, history and also the tribal mythology of The Troubles with unrelated struggles in faraway lands. Robert took pains to emphasize that the Catholic versus Protestant struggle in Northern Ireland shouldn’t be understood as a religious one. Indeed, I never learned whether or not Robert attended Mass, he never spoke of the role of the Sacraments in his life and there wasn’t a shred of theology anywhere to be found. The same could be said for his Protestant counterpart, Mark. Instead, he presented The Troubles as an anti-colonial, anti-imperialist battle of oppressed Catholics against the colonisers — the British Protestants. Everywhere I looked on Falls Road, the legacy of The Troubles was framed in this context. At times, the political parallels felt strained and tenuous.

The other international parallel that kept surfacing in the tour was the Berlin Wall. The grey slabs smeared with graffiti do invite this comparison. But as I began chatting with a German visitor on the tour, I discovered that she felt much the same way as I did about the parallel being drawn — only she was understandably more passionate about the issue. In Cold War divided Berlin, the Wall wasn’t demanded by residents to exclude the other side. It was imposed by politicians and the Soviet Union to keep one side in — stopping East Germans from exacerbating the brain drain by leaving. The Berliners didn’t cage themselves in due to tribal differences with their neighbours. They didn’t turn their backyards into veritable prisons. Most of Belfast isn’t at all like the Falls Road/Shankill Road neighbourhood of the city — not to mention either the rest of the United Kingdom or the Republic of Ireland. I kept wondering why anyone would volunteer to live like this when one could leave. Perhaps the pull of community is that strong.

The most engaging part of the tour, at least for this visitor, was when Robert spoke with passion of his involvement in the Falls Road community today. On the one hand, he’s an activist with Sinn Féin. He showed us party headquarters. On the other, he’s engaged in reconciliation initiatives — bringing together Catholic and Protestant youth. He uses the Clonard Monastery Youth Centre and funding from the EU Peace and Reconciliation Fund. This includes some one billion euros in support for ex-prisoners to engage in the difficult work of reconciliation.

In the Clonard Monastery Youth Centre, Robert tries to convince Catholic youth to see policing as a respectable career — rather than a career for traitors or the terrain of the enemy. He also speaks to youth about the importance of active listening to the other side, in order to better understand why they fear a united Ireland.

The Irish peace process, in fact, started at this monastery in 1988. These were secret talks led by Father Reid. US President Bill Clinton also met Jerry Adams here. Hearing of this legacy and of Robert’s reconciliation work, as well as the references to the Berlin Wall, it wasn’t surprising that the question of when this wall might come down came up in our group.

“The further away from the wall you live, the more you want it to come down,” Robert said. “But when you live here, you live in reality.”

We arrived at gates that Robert dubbed “Checkpoint Charlie.” Again, the Berlin parallel was tempting and perhaps understandable, but fundamentally inaccurate. This is where Robert handed us over to Mark. The two men –around the same age — spoke briefly, shook hands and that was that. Mark’s narrative was one of being misunderstood by a world that has “bought in” to Irish Catholic victimhood, whilst neglecting the Protestant victims of terrorism. It was a defensive stance. Parts of Shankill Road were veritable shrines to victims of terror. While along Falls Road, we were reminded of other struggles of oppressed people and international parallels, Shankill Road was about loyalty: to the memory of the dead and to the sacrifices of the World Wars, to King (or Queen) and to country.

Mark is a Loyalist and, like Robert, a prominent member of his community. That became apparent to us when during the tour several carks honked as he led us through the neighbourhood and people greeted him. He spoke of the 7.3 km peace line and how to this day, there is no mixing at all between the two communities. People do not live, eat or socialize together. There are no shared pubs nor any shared shops. And both communities retain separate schools and community centres. As a general practice, two of everything is built.

Mark referred to the area as having been the killing fields of Ireland. He was born here in 1963 and displays a fierce pride in what he portrays is his besieged and aggrieved community. The IRA bombed the Protestant community 17 times — shops, a library and a leisure centre were all targeted. A total of 317 Protestant civilians were killed by the IRA and the last of these deadly attacks occurred in 1993.

We were provided raw, even graphic detail on how the IRA attacks devastated Protestant civilians; how Napalm bomb attacks burned alive 12 people in a restaurant, including an infant. Mark spoke about how Protestant people were left to suffer in their own country and how the Good Friday Agreement allowed murderers out of prison. People who once committed violent offences now sit in government, he added.

Mark spoke about what he and his community believe to be the glorification of terrorist groups and the forgotten atrocities. He reminded us that the IRA is not gone and did not disband. He also believes that illegal weapons remain at the disposal of members of the IRA. He quoted a number during the tour — that some 6,300 IRA members were let out of prison 24 years ago. He believes that Sinn Féin, now a dominant political force in Belfast politics, is linked to a terrorist organization. The IRA’s goal remains the same, according to Mark — to remove all the British from this region and to unite Ireland. Along the side streets of the Shankill Road neighbourhood, the modest family homes are adorned in the Union Jack.

Several of us asked Mark about reconciliation efforts and he said that he’s all for them. In fact, this year Mark invited the Catholic Resident Association to participate in the Jubilee festivities with Protestants. He proposed transporting children from the Catholic community by bus. The Catholic association declined the invitation. We asked him if he’s ever had a drink, a coffee or a meal with Robert. After all, they have been collaborating on this tour for many years. I think Mark thought that to be a silly question. He’s not friends with Robert and he likely never will be. They don’t socialize and that won’t change in the future. Instead, they’ll continue sharing their stories and speaking of reconciliation — a desire on a future horizon — on opposing sides of the wall.

Wow Chris. There is in all of that a great sadness – they take part in tours but without reconciling with each other. So much pain. I wonder what reconciliation might look like there – probably every bit as painful as it does here….