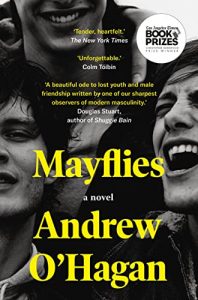

Andrew O’Hagan’s novel Mayflies is about departures — and about the liturgies that precede them. In the first half, set in 1986, a music festival in Manchester is the last hurrah of boyhood before a close-knit group of young men head off on the divergent paths of adult life. In the second half, thirty years later, they gather again at Tully Dawson’s midlife wedding — celebrated against the shadow of his terminal illness. It’s more the closing chapter of Tully’s life than the start of a new one. O’Hagan’s prose is full of life and piercingly sad. The novel doesn’t sentimentalize loss, suffering, illness or nostalgia for a lost youth. Yet Mayflies certainly isn’t cold or devoid of emotion either. A sort of clipped and raw emotion is always there, behind each scene. It’s not overthought — instead rising organically from the dialogue and from the reflections offered by the narrator and protagonist, Jimmy, Tully Dawson’s childhood friend.

Tully is a couple of years older than Jimmy. They grow up together in Ayrshire, just outside Glasgow, amidst miners’ strikes, labour strife, unemployment and the economic hardship of the Margaret Thatcher years. The book opens with a callous act, when we learn that Jimmy’s parents had simply abandoned him, leaving the teenage boy alone in the council home the family once occupied. Jimmy tries not to think about his parents much, deciding stoically that rather than becoming a victim of neglect, he would rather be seen as having “divorced” them. Tully and his mother Barbara treat the orphaned teenager as a member of their own family. Meanwhile Jimmy’s presence helps bring light to a house over which Tully’s physically and mentally ill father casts a long, dark shadow. The young men in Mayflies embrace socialism and a staunch critique of Thatcherite Britain, all with the fiery passion and idealism of youth. Yet in many ways they’re alienated from much of their parents’ working class generation — mainly as a result of their education, their tolerance of difference, by being so philosophically-inclined and by their choice of music and culture.

The novel really takes off when Jimmy, Tully and their friends take a trip to attend a weekend music festival in Manchester. They treat the trip to the industrial northern English city as though they were pilgrims en route to some rendition of Mecca. One of the most colourful and ultimately tragic characters in the novel is Lincoln “Limbo” McCafferty. The narrator likens him to Anthony Blanche from the novel Brideshead Revisited. Readers who have read the novel or seen the BBC series from the eighties will find that the comparison evokes the image of flamboyance and youthful eccentricity.

The heart of the novel, however, is Tully Dawson. He’s a cheeky troublemaker, a charismatic leader, a clever survivor and a big brother figure to Jimmy. Tully and Jimmy make a fantastic pair of characters. Of the two, Jimmy is more measured, but still willing to go along with Tully’s antics. They are both deeply likeable, even when they make poor decisions.

In Manchester, Tully takes care of Jimmy. He arranges the trip, pays for Jimmy’s way, finds shelter and devises a way for his friend to enter the sold-out festival after he loses his ticket. Tully puts on a show of bravado and good cheer, but in one sense it really is mostly a show. His father back home in Ayrshire had just suffered a heart attack, but he decided to take the trip anyway. Not too far under the surface, his father’s illness and his poor relationship with the mostly miserable man upsets him.

While Tully took care of Jimmy in Manchester, thirty years later the tables turn. In 2017, Tully is an English teacher in Glasgow and Jimmy is a writer in London. They reunite as Tully shares the news of his terminal cancer diagnosis. Here the narrative moves from the friendship of a group of young men to the relationships between two couples: Tully and his girlfriend Anna, and Jimmy and his wife Iona.

Grief over the diagnosis, deep anxiety over Tully’s decision to seek a medically assisted death in Switzerland, and the desire to find meaningful ways to spend the final months form the backbone of powerful dialogue and prose. Assisted death poses a profound emotional burden and a sense of guilt for the loved ones to be left behind. At the same time, amidst the uncertainty, it offers the promise of relief for the afflicted. These tensions are presented exceedingly well and delicately in Mayflies. The struggles are fleshed out mostly in the dialogue.

The only interaction where that struggle could have been more present is in Jimmy’s discussion with an Anglican priest called Gemma who he had befriended. Initially, there’s a nice bit of dialogue.”Good for me to talk to a person of faith,” Jimmy writes in a text. “Good for me too,” she replied winsomely to Jimmy, a lapsed Roman Catholic. He goes to her seeking solace and reassurance as he faces his friend’s request. She supports him in his decision to assist Tully in seeking death. It seemed to me that the Anglican clergywoman was perhaps too quick and too confident in speaking of medically assisted suicide as an act of mercy. Everyone else in the novel wrestled uncomfortably and to varying degrees with Tully’s decision.

A quiet faith dynamic weaves through the novel. In the first section we’re introduced to the cultural Christianity of 1980’s working class Britain. At times the description of working class Glasgow and of Manchester reminded me of the 1994 BBC film Priest. The symbols of the Christian heritage are woven into the fabric of everyday life, even whilst church attendance and an outward faith life are not. At one point, the teenage boys muse about the colour of heaven — is it blue, as eccentric Limbo thinks (and the character’s name is a reference to the Catholic theological concept of Limbo) or is it black, as Tully suggests? There are two minor characters appearing in the second half of the novel that mirror the quiet faith that is present throughout O’Hagan’s work. Fiona, Tully’s sister, and her husband Scott embody a quiet but confident belief in God and in eternal life. Fiona “brought decorum, a well-rehearsed tolerance of life’s unfairness…Fiona and Scott weren’t Bible-bashers, but they were that more persuasive thing, quiet believers.”

Two central themes in Mayflies are community and escape. Messy or complicated family lives lead the characters in the novel to find community and support through friendship. The grim economic realities of 1980’s working class Scotland and England propel the boys to seek reprieve in music, the arts, reading, learning, the bar scene, alcohol and drugs. Three decades later, when Tully becomes sick, escape takes the form of an intimate wedding ceremony with friends, a trip to sun-drenched Sicily and the option of assisted death in the heart of continental Europe. And alongside community, there is also conflict — perhaps necessary, given that boundaries are part and parcel of community. There’s generational, economic and socio-cultural conflict, as well as tension between the Scottish and English.

Sprinkled in Mayflies are cultural references to some of my favourite twentieth century British authors, notably Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene. I’ve only just discovered the works of O’Hagan, who has found inspiration in these twentieth century classic novelists too. Mayflies proved to be a compelling introduction to O’Hagan’s work.

Wow, this novel sounds like an awesome read! You describe the storyline in a well thought out and calculated manner, which has left me anxiously waiting to find out what happens in the end. You have once again sold me on a book to read, your delivery of the synopsis has got me ready to go to my local Cole’s bookstore as soon as possible. I enjoyed reading your narrative due to the fact that it was simple, yet powerful. The most effective and attention grabbing portion of this piece is the Dr. assisted suicide, as this is a sensitive topic to speak about for almost everybody. Based on what you say in your article, it is obvious that Jimmy is deeply saddened by Tully’s thoughts of medically administered death. The scene in which Jimmy speaks with Gemma; who expresses the view that Tully should in fact follow through with his idea, is an interesting dialogue indeed. That would be due to the well known declaration made by religious figures, that suicide is a sin so severe that whoever commits it is banned from entering the gates of Heaven. In this post, you have brought attention to the difficult conversation that almost always arises concerning terminal illness, and medically assisted death. I am very glad to see that some awareness is being drawn to this topic.

My grandma has been fighting terminal cancer, and she spoke with us about looking to go that route not long ago. My entire family was divided between those who were opposed to such a thing, and others who were accepting of grandma’ choice… We still haven’t all come together since then. All in all I would say that your commentary on Mayflies is the flame to my moth. Thank you for such a great breakdown.