Graham Greene referred to his 1955 novella Loser Takes All as a “frivolity.” Yet that shouldn’t lead any reader to think that this book is throwaway pulp fiction. The story of a couple vacationing in Monte Carlo may be light-hearted fare, but the writing includes Greene’s celebrated, signature style: sharp dialogue, economical and precise language that paints a vivid picture, both of characters and of places, dry humour and people struggling with questions of conscience.

Bertram, an assistant accountant in his early forties, leads an average life devoid of visible success. There’s nothing even remotely outstanding about him. He’s divorced and is now about to marry Cary, a woman about half his age, at an entirely conventional church ceremony at St. Luke’s in London — followed by a modest, affordable honeymoon in Bournemouth. When he tells Dreuther, his eccentric, scatterbrained and wealthy employer about his wedding plans, he’s told that all of that sounds dreadfully “classical.” Dreuther offers to cover the costs of Bertram having his wedding and honeymoon in Monte Carlo instead, and they would join him on his yacht as well.

“…You must be married in Monte Carlo. Before the mayor. With myself as witness. On the 30th. At night we sail for Portofino. That is better than St. Luke’s or Bournemouth,” Dreuther decides, before he gets his secretary to bring him a glass of milk, to make all arrangements around the trip and wedding — but not to speak about any of this to him again, because he “wants to hear no more of it.”

A wedding in Monte Carlo is quite out-of-character for Bertram, but he tells Cary about the offer. This is when we have a dialogue that shows Greene’s spark as a writer. Cary begins:

‘Darling, I did want to be married at St. Luke’s.’

‘Think of the Town Hall at Monte Carlo — the mayor in all his robes — the, the…’

‘Does it count?’

‘Of course it counts.’

‘It would be rather fun if it didn’t count, and then we could marry at St. Luke’s when we came back.’

‘That would be living in sin.’

‘I’d love to live in sin.’

‘You could,’ I said, ‘any time. This afternoon.’

‘Oh, I don’t count London,’ she said. ‘That would be just making love. Living in sin is — oh, striped umbrellas and 80 in the shade and grapes — and a fearfully gay bathing suit.’

In this clipped, casual back-and-forth, Greene paints a picture of Cary with so few unnecessary words. Cary is youthful, with innocent questions for her much older fiancé. But she’s also mischievous and has an adventurous streak. She’s attracted to Bertram in part because he is of limited financial means. In London, they can only afford a simple lunch of cold sausages at a pub called the Volunteer and Cary — as far as can be from a gold digger — is perfectly happy with that. When they arrive in Monte Carlo and she comes across a “starving” French student who is proving utterly incapable of turning his luck around at the casino, she’s attracted to the “romance” of youthful poverty.

That poses a rather significant conundrum for Bertram. Monte Carlo is all about glitzy casinos and as an accountant, Bertram is all about numbers, systems, patterns and details. Although he doesn’t believe in superstition and luck, he’s drawn to the idea of developing a foolproof system to win big at roulette. Meanwhile, Dreuther never sails in as promised, at the agreed upon time. Bertram and Cary soon realize that they’re staying at a hotel that is well beyond their means. Without Dreuther’s support, they won’t have the money to pay their bill. Cary finds their poverty and predicament quite romantic and exciting. They dine on coffee and bread rolls, as they can’t afford anything else. And they evade hotel staff to avoid raising suspicion. Cary gets a thrill out of their precarious situation. But how would she react if Bertram’s system actually worked and he began winning?

Although a short, simple narrative, Greene’s characters are quite nuanced. We see Cary as youthfully naive, idealistic and innocent on the one hand, and at other times determined, worldly and cheeky too. In some contexts, Bertram is a bland, unambitious junior accountant heading towards hopeless middle age, while in other instances he shows fire, a fleeting temper and drive. And one of the most fascinating characters is the enigmatic and eccentric Dreuther. When we first meet him, he’s sitting quite literally in his ivory tower — in his ornate eighth floor office, from where he rarely descends and seems oblivious to the daily realities of his staff down below. A man in his ivory tower isn’t usually a very likeable character — but there is something endearing when it comes to Dreuther. He’s so genuinely out of touch and scattered, that it’s quirky and even sweet. He’s fascinated by the most average things in the lives of others, although he doesn’t stay intrigued for long, as his mind wanders in many directions. Greene paints an apt picture. He describes how hearing of ordinary things hits Dreuther with the “shock of novelty” and how he “entertained them as an imprisoned man entertains a mouse or treasurers a leaf blown through the bars.” Other than underscoring the elderly man’s eccentricity, Greene also suggests that wealth and stature may in fact imprison, rather than serve as the winning ticket to freedom.

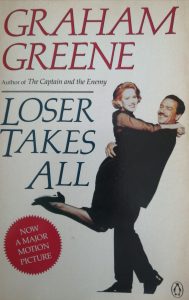

Loser Takes All was turned into a film twice — on the first occasion right after its publication. Its plentiful dialogue makes it well-suited for the silver screen. This book, however, is also a reminder not to dismiss works that Greene himself categorized as frivolities or entertainments. They include in small doses this prolific novelist’s best traits.

Be First to Comment