British author Christopher Walker has built a life for himself as an expatriate in Bielsko-Biała, a town in southern Poland, where he has lived for over a decade and where he teaches English. His fictional work There There, which he sent me in exchange for an independent review, offers relatable storytelling for those of us who have experienced the authentic, unglamorous and sometimes gritty side of solo travelling in continental Europe. Walker starts us off in Kraków’s suffocating summer heat and eventually takes us to France in the two interconnected novellas that comprise this anthology. The prose is often atmospheric, as intricate details come together to provide us with a vivid taste of the place we are seeing through our narrator’s lens.

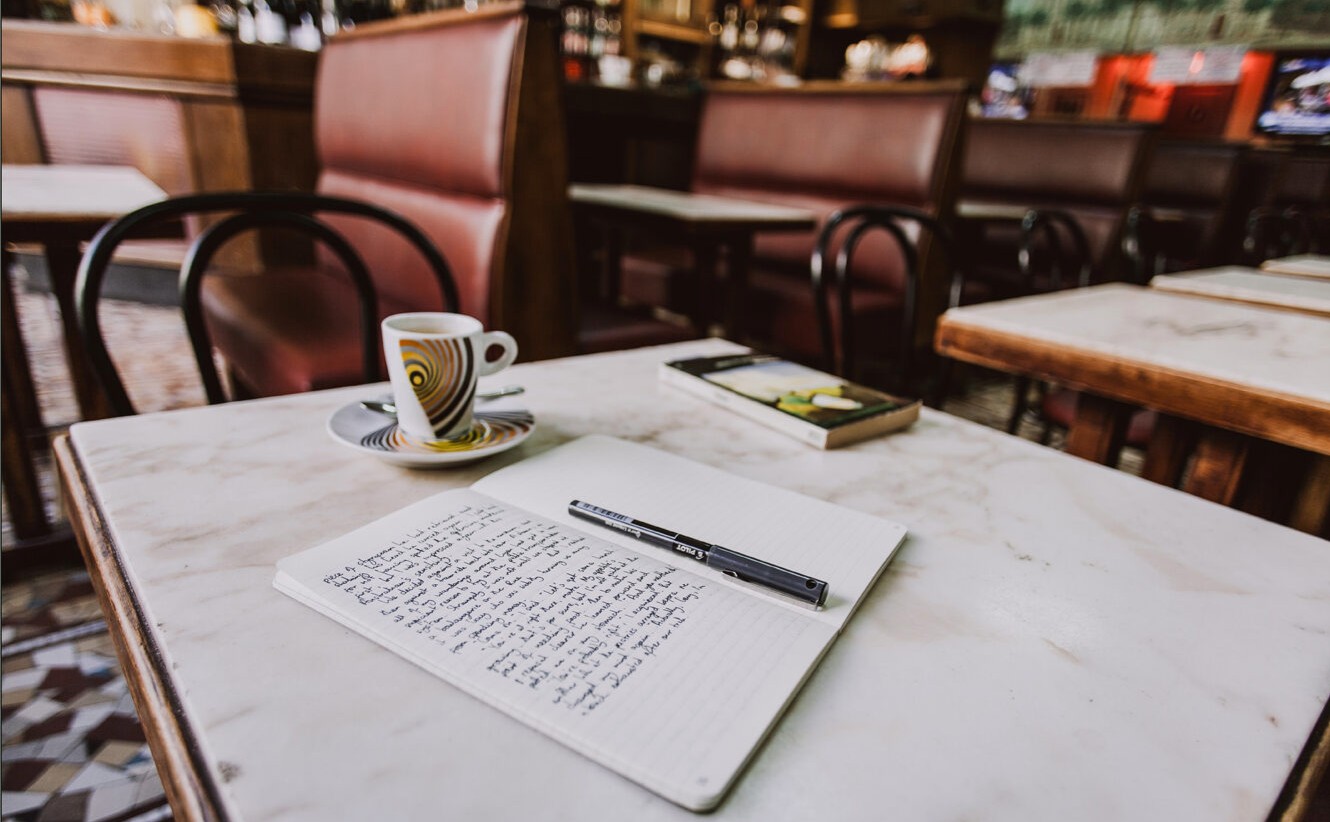

There is an understated, sometimes self-depreciating humour that runs through There There. In the first novella, social awkwardness characterises the narrator, which naturally gives rise to fiddly exchanges and situations. In one scene, the narrator, a photographer hired to capture a wedding reception later in the day, engages in the time-tested activity of the solo traveller with time on his hands: he sits on the terrace of a café with a book and coffee, not actually reading the book, and wondering instead how long he can just sit there lazily on this blistering summer day, while he engages in people-watching and eavesdropping. As is so often the case in Europe, the scene is one of aesthetically pleasing, quaint history of the town that surrounds the narrator, interrupted abruptly by a brutish manifestation of modernity. We read:

Just as the scene was reaching the pinnacle of perfectness, with the air still, the sound of a small boat chugging down the Vistula, the smell of the eggs wafting about… a delivery van arrived. Noisily it reversed onto the curb of the pavement opposite us, and a heavily tattooed man jumped down from the cabin to begin unloading crates of food for a sushi restaurant.

The narrator, a British expat, sparks a conversation with the English-speaking couple seated next to him. As a solo traveller, he seems to have some desire to engage in social contact, but doesn’t yearn to get sucked into a long and inane exchange. The woman next to him, who fancies herself a novice art photographer, shows him the photos on her camera, convinced of her undiscovered talent. All of us have “been there and done that,” so the speak — showcasing what we believe to be our photographic skill or being on the receiving end of someone else’s enthusiastic display. The narrator, however, commits an honest slip of the tongue about the quality of the photographer’s work, followed by a clumsy attempt to redeem himself and stroke her ego, derailing the exchange onto awkward terrain.

Many of the narrator’s exchanges with others are misinterpreted by those around him, he doesn’t fit in and he treads along the very edges of society. He is often unable to connect meaningfully with people in his midst, and his mind is in a different place altogether — perhaps most evidenced by his frequent and sometimes obscure references and metaphors involving literature, history and antiquity. The narrator is marginalised, although it isn’t clear what role he plays in his own marginalisation. After a very public confrontation one evening along the Vistula, where he takes a photograph of a woman without her permission thus sparking her ire, his predicament is laid bare and this is one of the few times in the story that we learn a little more about what the narrator looks like:

“Great sobs heaved their way from my chest, and I sank to my knees…I had no audience for my own confrontation with misery. Who would have wanted to witness a fat, balding, sweat-soaked man pour out his grief on the bridge with all those lovers’ locks? Beyond me the beautiful city of Kraków began to thrum with the youthful energy of a tempestuous summer’s night…”

In the second novella, Walker takes us to Lyon, France. We learn that the narrator is on a brief, but much needed getaway, again travelling solo, with his English expat family back in Poland. Travelling with his modest Polish savings, the narrator seeks a “Hemingway experience,” notably a Bohemian séjour in continental Europe’s cafés, writing away and letting creativity flourish alongside occasional shots of espresso. Sartre makes a guest appearance from time-to-time, arriving in a cloud of cigarette smoke. The narrator aptly points out that the Hemingway experience is often more romantic in retrospect than when lived in real-time. Wondering how long one can get away with occupying a seat in a café whilst consuming merely a two-euro espresso is a delicate and sometimes stressful game. Being a starving artist is a strangely appealing literary reality on paper, but it seldom is so in real life. The narrator meets an Australian called Guy — the two are of a similar age, both of them are mostly broke, but the Australian is far less interested in intellectual pursuits. They explore Lyon, they engage in storytelling, the narrator assists in a matchmaking pursuit involving Guy and a woman called Celeste, while as readers we explore France and the inhabitants though the narrator’s eyes.

Walker’s novellas reveal much more about the locations being visited than about the narrators themselves. Details on the narrator’s physical characteristics, their backgrounds and personalities are relatively sparse. Perhaps it’s fitting to know so little about them for a few reasons. In the first novella, the narrator is a photographer, while in the second he is a proofreader. People in both of these professions work behind the scenes. They are helpers in the shadows whose job it is to present someone else to the world, and to ensure that their patron is depicted in the best possible light. The story is never about the proofreader nor the hired photographer — it is about how they edit and filter the world that we see, either through their lens or through their pen.

The second reason for the relative lack of description of both narrators may be a reflection of the nature of travel itself. Walker intricately sets the scene when describing the Café de la Cloche in Lyon, but leaves much about the narrator himself a mystery. When we are tourists in a foreign city or country, we roam with a certain degree of anonymity. We are necessarily an unknown entity observing the city and society that we visit from the sidelines. We are never part of the fabric of the land, but rather an interloper — sometimes rather a bother for locals too — as we see, learn and interpret the foreign world that surrounds us, before departing. We come and go, and we are a nameless, fleeting presence to the local inhabitants. By sharing so little descriptive material on the narrators, Walker seems to highlight this reality of being a stranger in a foreign land.

There There is a heartfelt reflection on the nature of travel and how we process it both during our trip and upon returning home. As the pandemic bars most of us from travelling, Christopher Walker’s book is relatable and may even spark a little honest nostalgia as we realise that the gift of exploring new cities, countries and cultures may be one that has slipped through our fingers, at least for now.

Be First to Comment