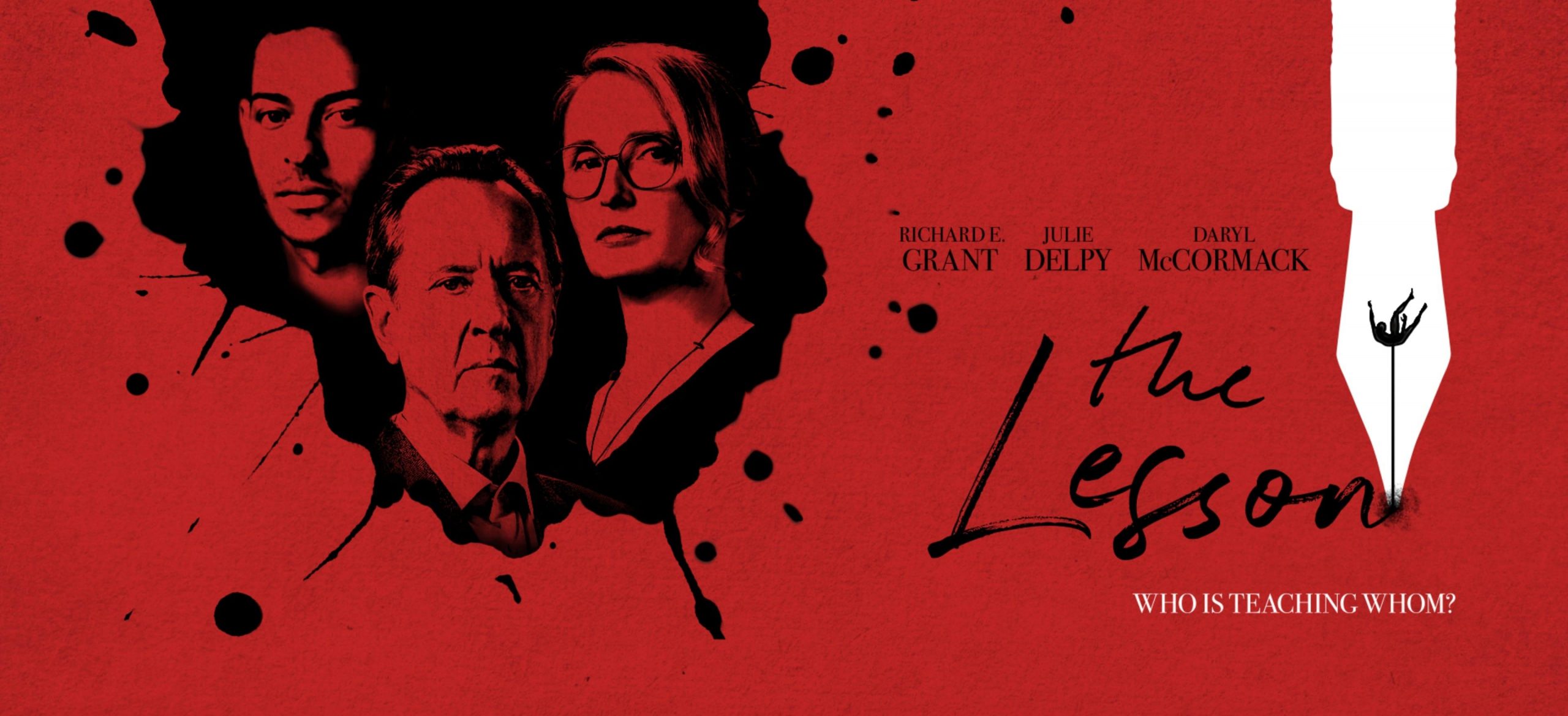

This cheeky British film — billed as a thriller — is in fact part mystery, part drama. It’s a slow burn set during the doldrums of summer and on the leafy grounds of an English country estate owned by a revered and secretive novelist. The story is told mostly from the point-of-view of the young, fledgling author and private tutor Liam Sommers, played by Daryl McCormack. He is hired by established author J.M. Sinclair (Richard E. Grant) and his art curator wife Hélène (Julie Delpy) to prepare their teenage son Bertie (Stephen McMillan) for Oxford University’s entrance exams in the competitive literature programme. Bertie’s parents are ambitious, career-oriented, aloof and emotionally absent from their son’s life. Perhaps not surprisingly, Bertie displays some teenage surliness, especially when he first meets his tutor. Not only does he have a cold family life, but he faces the pressure from his mother to get into Oxford at all costs, alongside his father’s dismissive, disinterested demeanour and the family tragedy of his older brother’s tragic death, which hangs over the household.

J.M. Sinclair’s oft-repeated motto, “good writers borrow, great writers steal,” alerts the viewer that all may not be what it seems in the life and work of this celebrated novelist. Sinclair is a fraud and he all but discloses this to his adoring audiences when he keeps sharing his motto. Yet everyone is so enamoured that they fail to see it for what it is: basically, an admission. Unlike his unattractive conduct in private, in public interviews Sinclair has charisma. Interestingly, some of his mannerisms and style of speech remind me of former Prime Minister Tony Blair. Sinclair, however, dupes his fan base. It’s hardly the first time that something is right in front of us, in plain sight, yet celebrity culture or deference to cultural leaders is so intoxicating, that people become blinded to the obvious.

As an aspiring novelist, Liam Sommers looks up to Sinclair. Being hired to tutor Sinclair’s son and to spend the summer living on this author’s estate, must have been akin to winning the lottery for a talented young writer yet to land a publishing deal. Liam’s work, however, extends beyond tutoring. He’s tasked by Sinclair to help him with his IT troubles, whenever his printer or computer acts up. That’s when Liam begins to see Sinclair’s true face.

Directed by Alice Troughton, this film offers some sharp acting, as well as lush and atmospheric scenes. The musical score by Isobel Waller-Bridge has a classy, playful, continental European flair to it. The film celebrates the rich body of European art and culture, even though Sinclair’s habit of playing Rachmaninoff during the family dinner one night and then Beethoven the next, is mostly a sign of his snobbery. He’s painfully condescending, affected and arrogant. But the celebration of European cultural history is present in other, explicit ways too. Hélène plays Tchaikovsky on her piano and has a sculpture that reflects on the Italian sculptor Bernini. This family and their lifestyle is unabashedly high-brow, but that doesn’t mean that the story retreats from the realities of the contemporary world, including the role of technology in the writing and publishing process.

The film’s script was written by Alex MacKeith and I think he accomplished a difficult feat. The protagonist, Liam Sommers, is at the centre of a fish-out-of-water narrative. He’s a young Irishman of modest financial means, still at the very beginning of his writing career, working and living in the exquisite home of a privileged couple in England. It would have been so easy to go with the trope of the shy, wide-eyed, subservient and innocent outsider lost in the ornate lifestyle of the rich and famous. Mercifully, Liam is deferential but not a push-over. He’s green as a writer, but he’s not naive. He stands his ground and has a unique gift: a nearly photographic memory. There’s strong, life-like dialogue and relationships between Liam and Bertie, who warms to him, opens up emotionally about the death of his brother Felix, and sees in his tutor something of a surrogate big brother. Hélène’s relationship with Liam is rich too — she’s his shrewd employer and forces him to sign a nondisclosure agreement. But Liam is also more comfortable going to her than he is to the harsh Sinclair. There’s some sexual tension as well between the two, and both need each other in different ways.

The Lesson touches on themes that any writer — aspiring, emerging or established — will recognize. The film explores the importance of an author observing their surroundings and incorporating what they see into their stories. Is that “theft” or a lack of originality? The most memorable fictional characters are usually amalgams of real people in the author’s life. They’re not just figments of their imagination divorced from life experiences. Is the boundary between memoir and novel a porous one? Sinclair, like many authors, recoils at presumptions that he’s more present within his stories, as a protagonist, or that they incorporate his family tragedy, rather than the novelist simply being the creator of these fictions. The film also shows how relational the publishing industry can be and how difficult it is to break in, while the ones who sell and have built a name for themselves are at the receiving end of adulation. It can be a harsh world for aspiring authors. There’s a powerful scene when Sinclair does Liam the great honour of reading his manuscript — and then absolutely demolishing it, and the young author himself.

I was fortunate that the iconic ByTowne Cinema — the last remaining movie theatre in downtown Ottawa, located on an increasingly distressed Rideau Street — screened The Lesson when no other cinema in the city or region did. Amidst the loud blockbusters, the fantasy sci-fi films spliced with computer-generated special effects, and the horror remakes, The Lesson is a quiet, thoughtful, darkly funny film set in the English summer. It’s a good choice for a summer afternoon on this side of the Atlantic too.

Be First to Comment