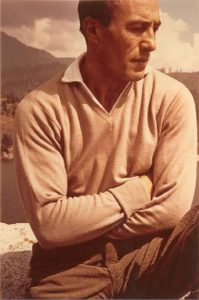

Family histories in Central Europe are complicated, especially in terms of what families choose to share with or withhold from the younger generations. Piecing together the various fragments to create coherent narratives of the past isn’t a straightforward process either. National borders have changed, regimes have come and gone, eyewitnesses may have died long ago and archives are not always easily accessible. Both my parents are Hungarians and my mother and father met in Canada. My father, Peter Adam, arrived in Canada as a young refugee in 1957, following the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution by the Soviet Union. He fled his home in Budapest with his younger brother, János (John) and settled in Montreal. A few years later, his mother (Mária) and my aunt (Éva) joined him in what, at the time, was Canada’s most populous city. My father began his Canadian life, like so many immigrants, as a taxi driver. Eventually, he went into business: opening commercial art galleries in Montreal and buying real estate.

On my maternal side, my grandfather — Ferenc (Frank) Oszlánszky — fled Hungary in 1957, first settling in Vancouver and then eventually relocating to Montreal. My grandfather, from the western Hungarian town of Pápa, was imprisoned under the period of Stalinism on charges of “conspiring to overthrow” the communist regime and was only released from prison after the popular revolt launched on October 23, 1956. Like my father, my maternal grandfather was one of some 38,000 Hungarian refugees who found a new home in Canada, in the immediate aftermath of the 1956 Revolution. He was, along with 200,000 Hungarians who fled to western countries, a “fifty-sixer.” My grandfather was finally reunited with his family–my grandmother, Margaret, and my mother, Alice–when at long last they were permitted to leave communist Hungary and immigrate to Canada in 1963.

For as long as I could remember, I was very much aware of my family’s ties to Hungary, how they had little choice but leave and how they built a new life in Canada. Growing up in Montreal, I spoke exclusively Hungarian at home with my parents and family–at least until I started attending school. After that, as is often the case, English crept into our conversations at home and the mixing of languages became the new norm.

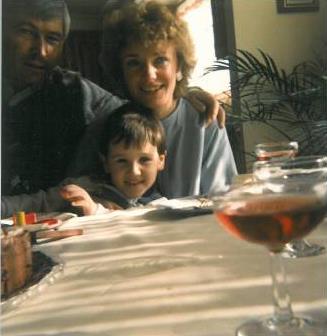

Our ties to Hungary, however, remained strong, especially through frequent visits from my great aunts, who were quite present in my life growing up, in the first family trip to the “homeland” in August 1990 and particularly after we moved to Budapest, Hungary in 1992, as my father sought new business opportunities following the country’s transition to democracy and a market economy. We returned to Canada in 1999, just in time for me to begin undergraduate studies at Montreal’s Concordia University.

There was one aspect of my family’s history that remained, until very recently, buried in silence. I recall that at the very end of the year in 1999, one of my father’s cousins, Endre Borsai of Haifa, Israel, wrote a lengthy letter to members of our family, scattered throughout the world. At the time, I never actually had a chance to read this letter, though I recall it caused some consternation with my father and my aunt and there were whispers of a disagreement about the family’s past, with particular reference to Endre’s claims of the family’s Jewish heritage. Having not read the letter myself, I recall leaving with the impression that the family had some Jewish lineage connected to my late grandmother Mária–although I knew that she did not consider herself Jewish at all. Both she and my aunt, Éva, were members of the Hungarian Presbyterian Church in Montreal and my grandmother was eclectic in her spirituality.

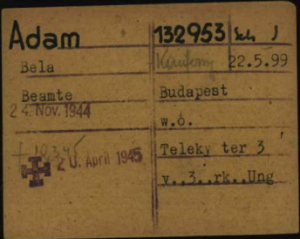

Only after both my father and my aunt had died did I begin to learn the truth about my family’s suppressed memories and Jewish heritage. Both my paternal grandparents were Jewish, by heritage. My grandfather, Béla Ádám, was deported and killed in Dachau concentration camp in April 1945 and my grandmother, father, aunt and uncle survived the Holocaust first in Budapest’s so-called “yellow star houses” and then in the Budapest ghetto.

I wrote an article in English about how I discovered this hidden family history and I also traveled to Israel in 2015 to meet with my father’s cousin, the first in the family to speak openly about the family’s past. I recorded with him a Hungarian-language interview on this aspect of the family’s history for posterity.

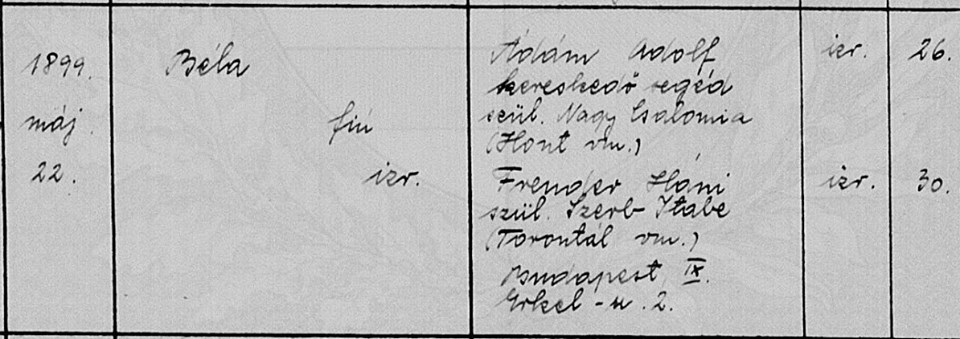

Piecing together a family history that had been suppressed for close to seventy years required testimony from the very few living members of my father’s generation, as well as the snippets of information that others in my family knew. It also required archival research and some “digging” on my part. The birth registries of the Budapest City Archives confirmed that Béla Ádám, born on May 22, 1899 in Budapest to parents Adolf Ádám and Háni Freuder was Jewish (as indicated by the abbreviation “izr.” or “izraelita’ in Hungarian).

Archival records, and indeed Endre Borsai’s written family history, confirmed that my paternal grandmother’s family was Jewish too. My great grandfather, born Aharon Wettenstein, changed his name in 1900 to Áron Borsai and my great grandmother’s maiden name was Laura Zimmermann. My great grandparents considered themselves Hungarian Jews and are both buried in the Jewish cemetery of Bánffyhunyad (Huedin), Romania. But in the multi-ethnic land of Transylvania they chose to effectively raise their children only as Hungarians. In fact, Dr. Áron Borsai, a prominent doctor in the area, built a reputation as philanthropist, promoting Hungarian culture–particularly literature–in Transylvania. He did this during a difficult moment in history for ethnic Hungarians, after Transylvania become part of Romania following the end of the First World War I and the signing of the Treaty of Trianon of June 4, 1920. The family home in Bánffyhunyad served as a venue for literary gatherings of Hungarian authors and artists, and Hungarian artist and author György Szántó (1893 – 1961) wrote about these gatherings in his autobiographical book Fekete éveim (My Dark Years). My great-grandfather also launched a scholarship for students enrolled at the Unitarian Academy in Kolozsvár (Cluj). More than anything, what I recall from what was told as a child about my father’s family was that they were patriotic Hungarians and supporters of the arts in Translyvania.

In the years following my aunt Éva’s death in 2013, I have been able to piece together the family suppressed tragedy in the Holocaust. In addition to memories and testimony from my father’s cousin Endre, of particular assistance were researchers of the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest. They were the ones who discovered that my grandfather had not, in fact, been killed in Mauthausen in late 1944, as originally thought, but in Dachau on April 20, 1945. And it was even more recently that the International Tracing Service (ITS) I was sent scanned copies of documents listing my grandfather, recovered from Dachau after liberation.

Before learning the full history of my father’s family, I gathered and shared a small handful of documents and information, published on an earlier rendition of this website. These were all in Hungarian and to preserve these too, I am including them on this redesigned site. If you read Hungarian and are interested in stories of one family living through the tumultuous history of early twentieth century Central Europe, you will find below the following:

- Endre Borsai’s farewell to my late father, Peter Adam, in Hungarian: “Búcsú Pétertől.”

- My father’s other cousin, Gábor Borsai, recounts the family’s history between 1920 and 1940

- Excerpt from György Szántó’s Fekete Éveim pertaining to my family.