Canadian author Kathy Clark’s new novel Ivan’s Choice tells a Holocaust story set in a country four thousand miles away. The Holocaust remains the most jarring period in living memory, at least in the West, but a memory that is fading as the number of elderly survivors dwindle. These two aspects of the novel’s setting — a distant time and place — require that particular attention be paid to making the novel accessible to contemporary North American readers, especially younger ones. Clark meets this challenge head-on by showing her readers both the human and the physical landscapes pockmarked by war. She does this through the first-person lens of a 13-year old Hungarian boy. As the protagonist, Ivan is both relatable and genuine — two characteristics essential to credible storytelling. And what lends the novel even more authenticity is that much of it is built around Clark’s family stories; she recounts through fiction what she learned of her parents’ experiences during the Holocaust in Hungary, and especially those of her biological father.

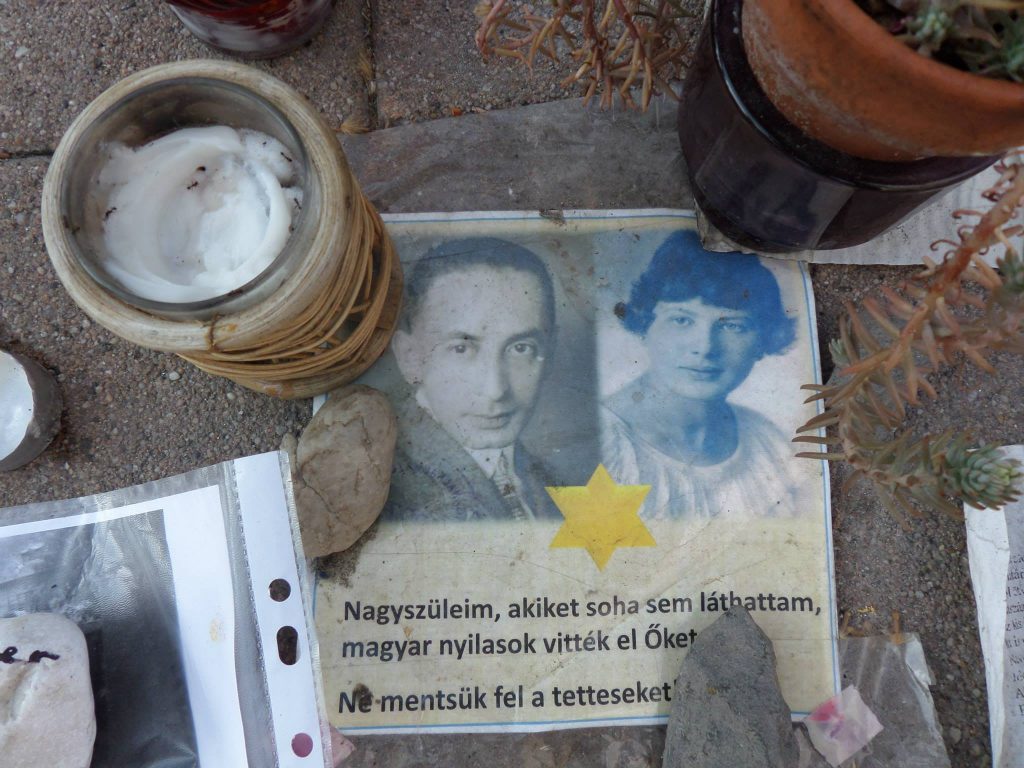

The novel opens in Budapest on November 5, 1944 — three weeks after the fascist and genocidal Arrow Cross Party is lifted to power by Nazi Germany, which had occupied Hungary earlier that year. By November 1944, the historic Jewish communities that dotted the smaller towns and villages in Hungary had been decimated by death marches and mass deportations to concentration camps — most notably to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where 430,000 prisoners were from Hungary. It’s been said that Auschwitz is the world’s largest Hungarian cemetery. The elimination of Hungarian Jews from rural areas and small-towns in a matter of months was possible due to the keen collaboration of Hungarian authorities with the occupying Germans. Until Ferenc Szálasi’s Arrow Cross rose to power on 15 October 1944, Budapest’s Jewish population had been spared annihilation, even though their fundamental rights were progressively stripped away in the prior months.

Ivan’s father is an enthusiastic Arrow Cross officer who speaks of Jews as “vermin” and “cockroaches,” and who had played a lead role in establishing the Budapest Ghetto. Initially, the young Ivan displays the type of muted discomfort that many Hungarians would have shared when they witnessed the persecution of Jews — especially when the Jews who were ghettoized or deported were ones the non-Jewish Hungarian might have encountered as neighbours, acquaintances or as friends. In Ivan’s case, his quiet unease was initially blotted out by the greater desire to please and appease his father — a stern man who he feared. The boy dons an Arrow Cross uniform and accompanies his father in carrying out the deportation of Budapest’s Jews. Ivan makes a point of outward displays of compliance as he rounds up Jews. But inside, he’s confused to see children, women and decent men he knew from his childhood, like the tailor who always treated him well, imprisoned in a ghetto that he thought must be for people who had done something wrong.

The inciting incident in the narrative arc comes near the beginning of the novel. Upon being instructed by his father to assist in rounding up a family for deportation, Ivan stumbles upon his best friend, classmate and neighbour Hendrik Varga in the ghetto. That’s where he learns that Hendrik, whose real name is Jakob Kohn, is Jewish. Like many in Hungary, the Varga family had changed their name and concealed their origins. The Vargas had papers to prove that they were Catholic, and Hendrik attended a Franciscan school, alongside Ivan. But the Holocaust was about race, not religion. Conversion to Christianity and even being assimilated into Hungarian national culture, as most of Hungary’s Jewish community was in World War II, usually would not be enough to escape persecution, deportation and death. As we learn, Hendrik had slipped into the ghetto without his parents knowing in order to visit his aunt Mimi and cousin Lilly who had been brought there, as they had not denied their Jewish heritage. Hendrik’s decision to visit the ghetto, although courageous and virtuous, also endangers and upends his family’s life.

Ivan’s parents are virulently antisemitic and his father is often rage-filled and volatile. What’s striking about his mother, however, is how she has a gentle disposition up until the subject turns to the Jews. Then she’s nearly as vicious as her husband. And, in the case of the Vargas, she is infuriated that she had been duped and had befriended them, never knowing their Jewish background. Ivan’s parents have few redeeming qualities for most of the novel.

Ivan’s mentor becomes a sixty-something Franciscan friar called Brother Ferenc. He displays compassion and humanity. Brother Ferenc encourages Ivan to view the world through a moral lens and to take personal responsibility as he approaches manhood. While Ivan’s father has Hendrik arrested and deported, and vows that the boy’s parents and maid will meet the same fate, Brother Ferenc agrees to hide the parents and the housekeeper in the monastery. Ivan soon learns that Brother Ferenc is cooperating with Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who is running a valiant mission in Budapest to issue forged Swedish protection documents to Hungarian Jews and to shelter as many as he can in various ‘safe houses’ established in the Hungarian capital. Ivan decides to share information that he gains from his father on what streets in the city are about to be raided by the Arrow Cross and the SS, in order to give Wallenberg and his people an opportunity to remove from these areas as many Jews as possible in advance. Ivan walks a fine line, deceiving his father into thinking that he is seeking to enthusiastically grow into an Arrow Cross officer just like him, while passing on information to Brother Ferenc and Wallenberg, in order to save the Jews of Budapest. On one occasion, Ivan accompanies his father on a raid and helps a group of children hiding in a cellar escape to safety.

The challenge in presenting historical events in young adult fiction is how to introduce nuance and avoid oversimplification of the history itself, while producing a work that is still accessible. Overall, Kathy Clark’s novel provides a level of nuance that goes beyond just a very broad Holocaust narrative. The novel speaks to the specifics of the Holocaust in Hungary and to the characteristics of Hungarian society more generally. Both the Vargas and Ivan Biro’s family are nominally Catholic, but neither household is particularly religious. This is an important detail to include, as Hungary — unlike Poland — was a broadly secular society. While Brother Ferenc is prophetic in opposing the persecution of Hungary’s Jews, the novel recognizes that the same cannot be said for the entire Franciscan community, or indeed for the entire Catholic Church. After the Vargas flee their apartment, Ivan’s mother is excited to enter it so that she might take some of the family’s valuables. One of the dark aspects of the Holocaust in Hungary is just how many ordinary Hungarians were quick to loot the apartments of Jews who had been deported. Another particularity of the Holocaust in Hungary presented well in this novel is how the Arrow Cross was so keen to deport or kill Jews as quickly as possible, that their speed and frantic enthusiasm surprised even the occupying Germans. One of the most horrific aspects of this history incorporated into the novel is how the Arrow Cross lined up Jews and shot them directly into the Danube river — sometimes tying up couples and shooting only one in the back of the head, who would then drag down and drown the spouse. And finally, the novel shows how the brutality of war, including the Allied aerial bombings of Budapest and then the Soviet siege, impacts the population as a whole. The novel mentions how Budapest residents would scavenge the bombed streets for dead horses and donkeys, bringing home the meat for food. Ivan ends up killing pigeons instead.

Reading Ivan’s Choice, I was reminded of a Hungarian song entitled “The Ballad of Dani Rosenberg” written by Tamás Pajor and performed in English by Ferenc Demjén, as part of the March of the Living in Hungary, in 2013. Like this novel, the ballad tells the story of two boys in Budapest navigating friendship, life and death against the backdrop of the Holocaust. The images were taken from the Hungarian Holocaust film Fateless (Sorstalanág).

Storytelling is perhaps the most ancient way to impart knowledge about the world around us, and about the past that still informs our society today. Kathy Clark’s novel takes what could be a distant, two-dimensional story found in a history textbook and makes it real to youth in Canada today. She does this while also exploring themes of responsibility, solidarity, sacrifice and loyalty — and how sometimes that which is legal may not be moral.

Be First to Comment