We learn the most about a person by how they respond to a crisis. Israeli film director Guy Nattiv’s movie on Golda Meir focuses on just three weeks in the life and times of Israel’s first female prime minister. Through the lens of the Yom Kippur War, we see Meir at both her toughest and also at her most vulnerable. We see her declaring over telephone that she’s willing to “slaughter them all,” speaking here of Egyptian soldiers encircled by the Israelis, and we also see her genuinely torn by the loss of human life. Helen Mirren, with no shortage of makeup and prosthetics, plays a convincing Golda Meir — in particular mastering the late Israeli leader’s American accent, influenced by having spent her first years in Ukraine and Belarus, then growing up Wisconsin, and living in what was initially Palestine and then Israel.

The story of Meir and the Yom Kippur War is framed by an initial political and military intelligence failing, and by the subsequent inquiry. Meir came to power in 1969, heading a left-centre Labor/Alignment coalition government. Nattiv’s film depicts effectively how Meir, her initially rather hapless Minister of Defense, Moshe Dayan, and cabinet as a whole was caught off-guard when a coalition of Arab countries led by Egypt and Syria launched a military attack on a Jewish high holy day, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The war began on October 6th, 1973, with the Israeli armed forces initially facing high casualties.

The film offers some nuance in how it presents the international significance of the war that lasted 19 days — and nuance isn’t easy in movies, so Nattiv’s team deserves credit. The world’s two superpowers assisted their respective sides in the conflict from the background, but wanted a ceasefire. The Americans, under the Nixon administration and in this movie represented by Henry Kissinger (played by Liev Schreiber), aimed to pull Meir back from taking a more offensive posture. The Americans and the Soviets had only four years earlier entered the period of Détente in the Cold War and sought to bring down the international temperature in the nuclear age. The American desire to see Israel compromise and accept a ceasefire was also motivated by appeasing the Saudis and the reliance that the United States had on Saudi oil. And in terms of domestic politics, the Nixon administration was rather busy with Watergate.

There’s a real sense of being alone in this film. First, there’s Israel as a country, unrecognized by its hostile neighbours and referred to as “the Zionist entity.” America is, of course, an ally but only to a point. Then there’s the almost suffocating loneliness of leadership. The burden of the war and the future of Israel rests on Meir’s shoulders. Her defense minister is depicted as falling apart and she finds herself trying to get him to keep it together. The scenes of her walking along dark, concrete, underground corridors or escaping to the roof for air really bring home how alone and burdened she was at the time. And finally, there is the loneliness of illness. Although kept a secret, Meir was battling a blood cancer, lymphoma, and was undergoing radiation therapy during the war. The film shows her walking through a hospital’s underground morgue each time she gets radiation in a restricted area of the building.

The movie depicts a relationship between Meir and Kissinger that is friendly, but also tense and not entirely trusting. Meir has suspicions about the US as well – she fears that they are all too willing to throw Israel to the wolves, as it were, should doing so serve their interests. Some of the scenes depicting Meir and Kissinger really humanize the two characters. Kissinger travels to Tel Aviv during the conflict and he meets Meir in her home. The two sit in Meir’s kitchen discussing the war and she makes Kissinger try her maid’s Borscht. Kissinger isn’t in the mood to eat, but as the dour maid looks on, Meir convinces the US Secretary of State that he hasn’t a choice and he must eat, as the maid is a Holocaust survivor. Kissinger complies and forces a smile as he tries a few spoonfuls. The maid eases up a bit.

There’s also a wonderful scene of Meir taking a homemade cake out of the oven and offering it to her generals and members of the cabinet, who gather in her living room. One of those generals is none other than a young Ariel Sharon — who would become Israel’s prime minister 30 years later. Sharon is a war hawk and Meir is both fascinated by his energy and drive, but also aware of having to restrain people with his disposition. Nobody eats from Meir’s cake during the tense meeting, but when everyone else has left the room, Sharon pockets a huge piece of it. That’s one of the moments in the film that brings a smile to the viewer’s face. The other is Meir calling Kissinger in the middle of the night to first inform him of the attack against Israel. The phone call begins with the usual bit of small talk — how are you doing, Golda? To this Meir replies, something to the effect of: “oh, you know, just some problems with the neighbours again” — as though she were tired of the people in the apartment upstairs dragging furniture across the floor at two in the morning.

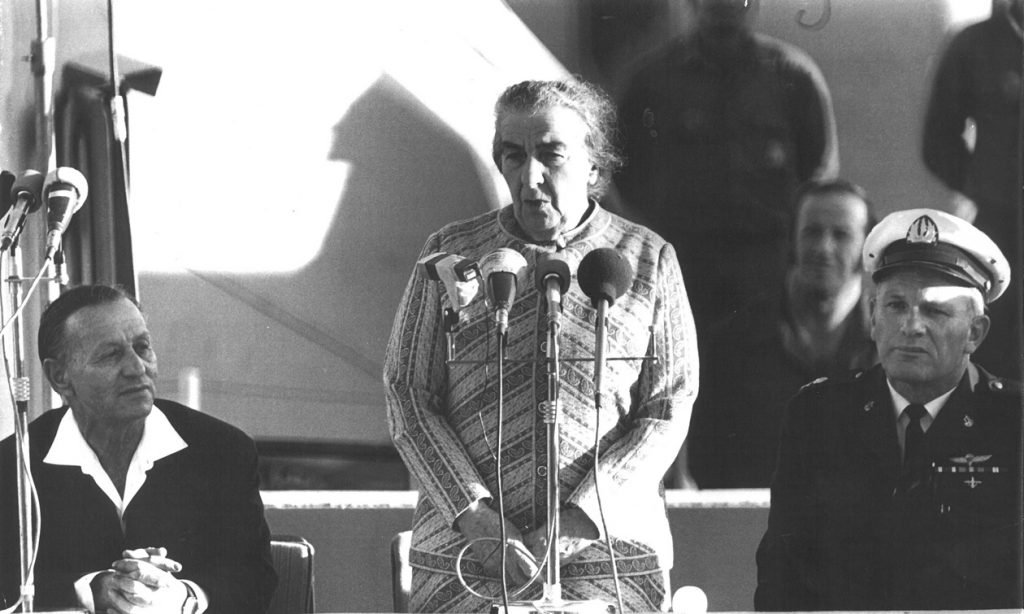

In one moment, the film depicts Meir surrounded by her soldiers, excited to have the prime minister visit. In many scenes, she is shown with her cabinet, surrounded by men in suits, all taller than her, but none more powerful, nor with greater resolve. One of the most memorable lines in the movie is when air raid sirens blare over Tel Aviv while meeting with her cabinet. She says to the men: “Well, I’m not going to get under the table, but don’t let me stop you.” While there are many scenes showing her resolve and strength, there’s also the constant presence of her illness. She smokes a cigarette on the hospital bed, right before her radiation therapy. She is reduced to silence as she walks through the morgue on the way to radiation and sees that it is filling up with the bodies of young men killed in the war. In one scene, her cancer treatment has made her so exhausted that she can barely get out of bed. She is literally pulled up by her personal secretary Lou Kaddar (played by Camille Cottin), as she must address the nation. And then there’s her stenographer whose son is sent to fight and is eventually killed; we see flashes of Meir’s empathy break through her tough exterior. We see her take responsibility for Israel’s initially flawed and slow response, which led to a loss of life, but we also see some of the fruits of the eventual and resounding Israeli victory.

Golda Meir wasn’t a saint and this film doesn’t provide a synopsis of her whole life and all her political views or statements. But mature adults don’t expect men to be saints when they hold political office and we shouldn’t hold women in politics to different standards or higher expectations either. And besides, many canonized saints had a track record of worse sins than many politicians. This film, however, weaves together Golda Meir the politician and the human — a woman in her seventies facing acute public and personal crises at the same time.

(The film Golda incorporates Leonard Cohen’s haunting song Who by Fire.)

Did you mention that she and Shimon Peres came to Palestine holding a visa as refugees. They held a Palestinian passport from 1929 till 1948. You should mention the whole truth about their story not only one side of it if you want to be honest.