At first glance it’s tough to like Hagar Shipley — the narrator of Margaret Laurence’s 1964 novel, The Stone Angel. This harsh, aloof woman is quick to judge and slow to forgive and understand. Yet she’s also self-aware; it’s her sense of quiet remorse that makes her likeable. And in Hagar’s twilight years, her fragility and vulnerability — her desperate struggle to overcome the awful indignities of ageing — soften the sharpest edges of her character, as does the knowledge that we gain of the tragedies she experienced in life.

Hagar is ninety years old. She lives in British Columbia with her eldest son Marvin and his wife Doris. It’s her house, furnished with her things, but her son and daughter-in-law have lived with her for many years and are now tasked with caring for her. Doris and Marvin would be empty nesters, with their own children now adults leading their own lives, but they’re hardly living their golden years. They are both in their sixties and as Doris grapples with her own gradual physical decline, she is Hagar’s primary caregiver, while Marvin continues to work as a paint salesman.

Doris, a religious woman, is dutiful in caring for Hagar, even as she becomes increasingly exhausted by the strain. She wakes at night when Hagar is unwell. She cooks for her, serves her breakfast in bed if she is too weak to come down in the morning, makes her tea in the afternoon and bakes her cakes and cookies. But Doris and Marvin are also paving the way to put Hagar into a nursing home — they plan this with care, caution and they find a good place for her. Marvin, a reserved type, is averse to conflict and finds himself caught between his increasingly exhausted and frustrated wife, and his stubborn mother who won’t hear of moving out of her home. She isn’t fully aware of how helpless she has become. To make matters worse, she’s suspicious of Doris and to some degree, of her son too. On the surface, she comes across as ungrateful, crusty, condescending and selfish. She looks down on both Doris and Marvin and it’s her upper middle-class upbringing that gives her license to be that way. When we dig a little deeper into the words, we can see how much of this is a way for Hagar to retain her dignity when faced with the indignities of her advanced age. When she’s outwardly harsh with Doris and Marvin, inwardly she mostly recognises that she’s being unfair.

It isn’t just the string of tragedies, particularly the death of loved ones, that has left a deep mark on Hagar. It’s how she missed opportunities to make peace with those who died that has marked her the most. Hagar never knew her mother, who died while giving birth to her. Both of her brothers died at a young age. She lost her father, then her husband and then her favourite son, John. In different ways, her relationship with all of them was strained. We’re guided through her hard life by virtue of flashbacks, memories and snapshots.

As I was reading The Stone Angel, I sometimes lost track of just how far back in history the stories of Hagar’s childhood and youth truly were. Ninety year old Hagar is looking back on her long life from the vantage point of the early 1960s. The scenes of her childhood in the fictional Manitoba town of Manawaka (inspired by Laurence’s own hometown of Neepawa) were from the last two decades of the nineteenth century. A detail here or a detail there would remind me of that pioneering era, when Scots Presbyterians settled in the Prairies. But curiously, the images and sensations of childhood as painted by Laurence were so relatable to my own childhood a hundred years later in a major Canadian city, or perhaps even to childhoods today, that it was easy enough to forget the distance of a long century. That’s either the sign of an exceptional writer or that the human condition survives the centuries largely unchanged — or both.

Class, and class-based divisions, are central to this novel and how the town of Manawaka is described in flashbacks. Hagar Shipley’s father, Jason Currie, was a proud Highlander and a merchant. As a founder of Manawaka, he was highly regarded and respected. He helped build the local Presbyterian church, bought cushions for his family’s pew and ran the town’s general store. When Hagar’s mother dies, Aunt Doll, his sister-in-law, becomes their housekeeper. Below him would have been someone like the town’s undertaker — an alcoholic called Billy Simmons who was rumoured to even drink embalming fluid in a pinch. Below the undertaker stood Lottie Drieser, sometimes teased as Lottie No Name, as she didn’t have a father. Far below the townspeople toiled the man that Hagar eventually married — the rough, even brutish farmer Bram Shipley who only ever showed genuine tenderness towards his horses and briefly after having sex with Hagar. Hagar’s father Jason effectively disowned Hagar when she married Bram, who he saw as a good-for-nothing. At the very bottom of the social order were Ukrainians and other eastern Europeans, who were referred to as Galicians, alongside the Métis, who are labelled Half-Breeds. It’s Bram Shipley, rejected and scorned himself, and his youngest son John who are the least prejudiced in this novel and willing to interact with the Eastern Europeans and the Indigenous. Ultimately, however, the Métis play a much more peripheral role in this book, than in Laurence’s later work The Diviners, where the character of Jules Tonnerre, briefly introduced here, reappears as a major character.

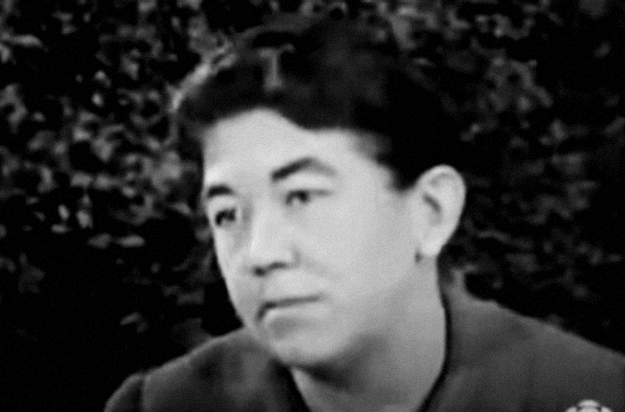

Laurence wrote The Stone Angel after spending several years writing works based on her experiences and observations living in Africa. Laurence sought to focus on the people she knew best: the Scots Presbyterians of Manitoba. In an interview with the CBC from the 1960s, Laurence explained:

I couldn’t go any deeper into the African mind, as it were, because I’m not African. I decided that I really only wanted to write about my own kind of people. I made up my mind that I was stuck with the Scots Presbyterians of Manitoba, for better or worse. God help them and me. I do have a very ambiguous feeling about my background. When I think of the Scots Presbyterians, the Prairie people, I always think of Moses’ remark at the Israelites: ‘you are a stiff-necked people.’ And this is true. We are a very stiff necked people. And there’s lots of things in that background that I don’t like at all. There’s a sort of suppression — a repression of emotions that I don’t care for. Yet there’s a kind of independence and strength, which I admire.

Fundamentally, Laurence is describing Hagar, who is the epitome of that stiff necked emotional repression and independence. But there’s something else that is revealed in The Stone Angel and hinted at in this interview. Laurence knows the Bible exceptionally well. Stories, images and references from Scripture appear throughout the novel. The elderly Hagar imagines hell to be like the sterile, loveless medical testing that she endures, and the instructions of the disembodied voices of healthcare workers who tell her to drink Barium and steer her through various x-rays. We read: “The pit of hell might be similar to this. It’s not the darkness of night, for eyes can become used to that. Another sort of darkness flourishes here — a darkness absolute, not the color black, which can be seen, but a total absence of light. That’s hell all right, and Rome is perfectly correct in that if nothing else.”

The fragile Hagar fights back to the extent she can by being curt and impatient with the seemingly cold, uncaring medical staff. But in a moment of grace, when the doctor says to her in a tired, gentle voice, “we’re only doing our best, Mrs. Shipley,” she sees him as human and overworked.

At various times in the novel, Hagar witnesses the inherent humanity of someone who otherwise frustrates or angers her. Her husband, Bram Shipley — labelled as “Shitley” by some in town — is often a profound embarrassment. She finds it too humiliating to attend church with him — although her own doubts and anger with God is reason enough for her to stay away. Yet she recognizes that he’s the only one in her life who ever called her by her name, Hagar, rather than “Mother” or “Daughter,” or something else. Bram, for all his roughness, treated her like an independent person. When he died, she buried him in the Currie family plot in the Manawaka cemetery — despite the fact that in life the Currie and Shipley families couldn’t have been further apart. We also see Hagar’s opinion of Bram’s former wife, Clara, change. Hagar hates her for much of the novel. But then, after Bram’s death, she finds a walnut wooden box with some of Clara’s most important personal items — including a tuft of hair from her infant who had died, fashioned into a small wreath. Suddenly, she begins to see the late Clara in a different light.

Hagar struggles to make peace with loved ones who had died. Her relationship with them was broken at the time of their death, making their passing even more difficult. It’s many years later that she begins the process of making peace. She found her father infuriating and was estranged from him when he died. Later in life, as she raises John, she begins to tell her son stories, with much pride, of the grandfather he never met. As a girl when one of her brothers is dying, her other brother asks her to comfort him. She simply can’t get herself to do it, and that sours her relationship with him. They rarely speak, and he has an untimely death as well. Although she loves John — certainly more than Marvin — she rarely shows it and her expectations of him are so high that it strains their relationship. When he travels back to Manawaka without her to care for his sick father — one who didn’t treat him particularly well — Hagar is at first irritated and confused. Ultimately, she’s moved by his gentle, unconditional concern and care for his sick father.

This novel spans generations and decades. There are scenes of Hagar and Lottie “No Name” growing up — the latter shunned by many, including sometimes by Hagar. Then as middle-aged women, they find themselves faced with the prospect of becoming family, as John prepares to marry Lottie’s daughter Arlene. Neither are pleased with their children, who are broke, getting married. A cup of tea and a chat in Lottie’s living — and perhaps also the trials of life — softens Hagar to her. We read: “how odd that we should have been friends, in a matter of speaking, all our lives, yet never once felt kindly disposed until this moment. There we sat, among the doilies and the teacups, two fat old women, no longer haggling with one another, but only with fate, pitting our wits against God’s.”

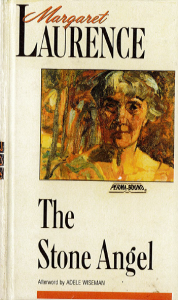

The stone angel, a monument erected in the Manawaka cemetery by Hagar’s father in memory of her mother, looms over the graveyard. It’s a lasting, sturdy witness to generations of human lives, relationships and tragedies. We’re told that it isn’t the only stone angel in the cemetery, yet it’s alone by virtue of its stature. It’s also double-blind — not only are its eyes downcast, but the eyeballs weren’t carved and given form. There is a key theme that weaves through the novel — that of humans having been created with eyes, yet lacking vision. And in a sense, Hagar herself becomes that stone angel. At ninety, she yearns to be sturdy, tough, proud and independent, while also desiring mercy and forgiveness for everything that she had left unsaid or unseen. She realizes that although she is still standing and observing the world around her, she’s very much alone. Her contemporaries have all died. And now near the end of her own life, despite having eyes that witnessed so much, she struggles to find the vision that might lead her to peace.

[…] In this scene from Margaret Laurence’s novel The Stone Angel, the elderly Hagar Shipley has escaped from her son Marvin’s house, in order to avoid being placed in a nursing home. She finds refuge in an abandoned building in the forest, along the coast. She has nothing but rainwater to drink until a stranger appears — Murray Ferney Lees. Hagar is suspicious and leery at first, but soon realizes that she has something in common with the stranger. This excerpt forms part of Chapter 8. Read my book review of The Stone Angel here. […]