A chance encounter can change the course of a life. That’s what happens to Ida Arnold in Graham Greene’s 1938 novel Brighton Rock. On a Whitsun holiday weekend, she has a fling with a frightened stranger on the cusp of death. Sun-drenched Brighton, with throngs of visitors from London enjoying a long weekend by the sea, is the seemingly innocuous backdrop for a story about mob life, murders and a seventeen year-old sociopath called Pinkie.

It’s unusual for a novel to begin from the point of view of a character who will die in the first chapter. Fred Hale’s murder, however, frames the story — as does his vulnerability in the last hours of life. He elicits empathy despite the fact that he may have his own chequered past. Fred is employed by a newspaper, The Messenger, in London. His job is to run a newspaper treasure hunt and promotional scheme. He travels to different locations in Britain and leaves cards in a variety of public places. When someone finds one of these cards, they can mail it to the editorial office and claim a cash prize. If someone identifies him in person as the so-called Kolley Kibber, and if that individual also carries a copy of The Messenger, the lucky reader may claim the grand prize.

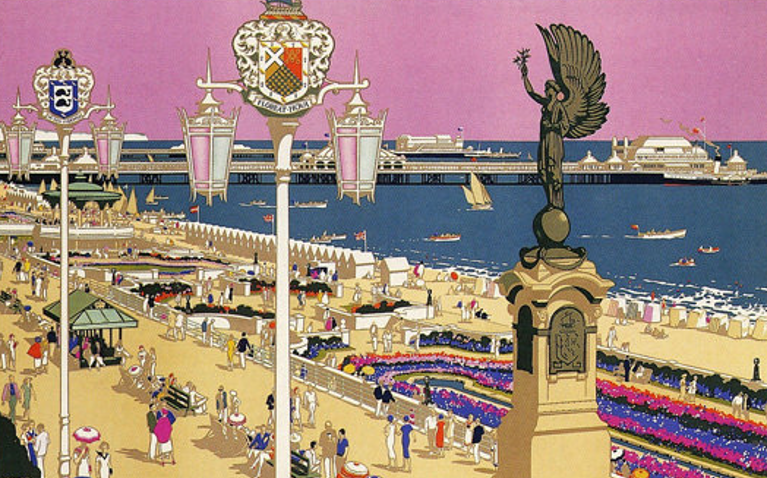

On Whitsun (Pentecost) weekend in May, he’s assigned to launch a treasure hunt in Brighton. This is a bank holiday in the United Kingdom during the 1930s when this novel is set. It’s also the unofficial start of the English summer. Brighton is teeming with Londoners who have come down for the day by train — the pier, the beach, the stick-shaped coloured candy called Brighton rock, souvenir shops, amusements, and a carnival atmosphere attract people of all ages. Fred Hale is in the paradoxical situation of needing to be recognized by a loyal reader as part of his job, while not being spotted by members of the mob who he knows are out to get him. He hopes that moving with the vast sea of tourists will shelter him from Brighton’s underworld. When he meets Ida Arnold, a middle-aged entertainer, he stares death in the face as he rides with her in a taxi. He kisses her passionately in the back seat, as he realizes that they are being pursued. He seeks comfort from this complete stranger in the moments before his life is to end.

Fred is killed, but his death is attributed to natural causes. Ida knows next to nothing about this man, but she’s determined to discover what really happened. He was supposed to wait for her while she slipped into a washroom for a moment, but by the time she had come out, he was gone — and dead. At first, she believes he was pushed into committing suicide. Later, she contemplates that it may have been homicide. Either way, there are a number of reasons why she decides to investigate. The most important of these is that she’s saddened that this stranger called Fred had nobody except for a distant cousin — he died alone and scared, and nobody bothered to ask any questions. When she attended his funeral and his coffin was rolled into the flaming crematorium, there was almost no one there. She is driven by compassion for a man who had been completely alone and abandoned. The second reason is that she believes in an “eye for an eye.” Someone is responsible for Fred’s death and that person must pay. She is convinced that there is both peace and joy in justice — including when it comes in the form of revenge. This is where ego mingles with a more altruistic quest for what is right. And the third reason: although Ida isn’t a Christian, she believes in ghosts and takes some instruction from a makeshift Ouija board. Fred’s spirit may be restless until justice is served.

In tandem with Ida’s determined investigation, we follow the story of Fred’s killer — Pinkie, also referred to as Pinkie Brown, and simply as “the Boy.” Pinkie finds himself the young leader of a ragtag gang after his predecessor dies. He’s intimidated and disgusted by the rival mobster, Mr. Colleoni, and his wealth — especially by the glittering and ornamental Cosmopolitan Hotel where he and his people stay. The Colleonis lead a strikingly different lifestyle from Pinkie who finds shelter in a decrepit rooming house.

With Ida hellbent on uncovering the truth, Pinkie is determined to get away with Fred’s murder and to survive Mr. Colleoni’s attempt to gain a mob monopoly in Brighton by intimidating the rival group. Pinkie is singularly focused on violence and cruelty — the only two things that seem to bring him some degree of pleasure. He doesn’t understand why others around him are drawn to both platonic and romantic friendships, he has no use for sex (he’s referred to as a “bitter virgin”) and he has an almost puritanical disinterest in alcohol. He carries in his pocket a small bottle of vitriol — sulfuric acid with which to disfigure the face of anyone who crosses him. “Cruelty straightened his body like lust,” we read.

Pinkie meets Rose, a sixteen year-old impressionable working-class waitress employed at the Snow café. After Fred has been killed, one of Pinkie’s men, Spicer, tried to cover their tracks by leaving the Kolley Kibber’s winning cards in various locations, including on a table in the café — as though Fred had duly completed his assignment before he died. Rose finds the card, but notices that the man who had left it in the restaurant looked nothing like the picture of Fred published in the paper after his death. In order to keep Rose quiet, Pinkie befriends her. He finds her repulsive and the idea of a romantic relationship even more so. Yet he believes he has no choice but to play the game. Eventually, he marries her simply to ensure her silence. Throughout the book his conduct, often despicable, is driven by fear and a desire to feel secure.

One of the things we learn about Pinkie is that he’s a Catholic, like Rose. It’s among the reasons why she’s attracted to him, even though he’s now a lapsed Catholic. He was once a choir boy, however, and the refrain he once sang keeps reappearing in the novel. In one of the early scenes with Rose, we read:

Suddenly he began to sing softly in his spoilt boy’s voice: “Agnus dei qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.” In his voice a whole lost world moved — the lighted corner below the organ, the smell of incense and laundered surplices, and the music — “Agnus dei,” “lovely to look at, beautiful to hold,” “the starling on our walks,” “credo in unum Dominum” –any music moved him, speaking of things he didn’t understand.

…

“I don’t care what you do,” the Boy said sharply. “I don’t go to Mass.”

“But you believe, don’t you?” Rose implored him, “you think it’s true?”

“Of course it’s true,” the Boy said. “What else could there be?” he went on scornfully. “Why,” he said, “it’s the only thing that fits. These atheists, they don’t know nothing. Of course there’s Hell. Flames and damnation,” he said with his eyes on the dark shifting water and the lightning and the lamps going out above the dark struts of the Palace Pier, “torments.”

“And Heaven too,” Rose said with anxiety, while the rain fell interminably on.

“Oh, maybe,” the Boy said, “maybe.”

Pinkie was living a veritable Hell on earth, so his imagination didn’t fail him when he tried to picture the eternal torments. In his understanding, he could commit whatever cruelties were necessary to finally feel safe and secure. And once he did feel safe, he would confess all of his mortal sins to a priest, thus gaining forgiveness from God. There’s a striking scene where he rationalises this, after being attacked by the rival gang. He is badly cut by their razors and bruised by their kicks:

It was impossible to repent of something which made him feel safe…When he was thoroughly secure, he could begin to think of making peace, of going home, and his heart weakened with a faint nostalgia for the tiny dark confessional box, the priest’s voice, and the people waiting under the statue, before the bright lights burning down in the pink glasses, to be made safe from eternal pain. Eternal pain had not meant much to him: now it meant the slash of razor blades infinitely prolonged…

A moth wounded against one of the lamps crawled across a piece of driftwood and he crushed it out of existence under his chalky shoe. One day — one day — he limped along the sand with his bleeding hand hidden, a young dictator…One confession, when he was safe, to wipe everything. The yellow moon slanted up over Hove, the exact mathematical Regency Square, and he day-dreamed, limping in the dry unwashed sand, by the closed bathing huts…

Although Pinkie’s faith is skewed, it’s also genuine. Graham Greene, a convert to Catholicism, seems to contrast this with a vapid, trite and disingenuous faith gaining ground in the thirties — one that tried to please everyone, but by doing so ultimately had nothing of value to say. Fred’s cremation service is the opening for Greene to critique spiritual platitudes. The nameless clergyman’s sermon is as intolerable as it is milquetoast:

“We believe,” he said, glancing swiftly along the smooth polished slipway towards the New Art doors through which the coffin would be launched in the flames, “we believe that this our brother is already at one with the One…He has attained unity. We don’t know what that One is with whom (or with which) he is now at one. We do not retain the old medieval beliefs in glassy seas and golden crowns. Truth is beauty and there is more beauty for us, a truth-loving generation, in the certainty that our brother is at this moment reabsorbed in the universal spirit.” He touched a little buzzer, the New Art doors opened, the flames flapped and the coffin slid smoothly down into the fiery sea…the clergyman smiled gently from behind the slipway, like a conjurer who has produced his nine hundred and fortieth rabbit without a hitch.

Greene presents the clergyman as a silly fraud. Ida’s reaction to him cements that picture. The funeral makes her reflect with refreshing honesty on her lack of faith in a life after death, and her belief in living it up here on earth. “She didn’t believe in heaven and hell, only in ghosts, Ouija boards, tables which rapped and little inept voices speaking plaintively of flowers. Let Papists treat death with flippancy: life wasn’t so important to them as what came after: but to her death was the end of everything. At one with the One — it didn’t mean a thing beside a glass of Guinness on a sunny day…Life was poor Fred’s mouth pressed down on hers in the taxi, vibrating with the engine along the parade.”

Faith isn’t the only contrast that Greene sketches so adeptly in his novel. Ida and Rose, for example, are two strikingly different women. Ida is self-confident, jovial, determined and much more experienced in life. Rose, on the other hand, is lost in her innocence. She is uncertain, subservient, easily impressed and willing to take abuse. The childless Ida sees all of this. She becomes quite maternal and protective in her dealings with the teenage girl.

Another contrast can be found between Pinkie and an older member of his gang, Spicer. Here, age and experience seem to breed conscience. Despite his crimes, Spicer certainly hears that still small voice inside. He grapples with a sense of guilt, which Pinkie interprets as weakness. Spicer thinks Pinkie, although brutal, is a loyal friend. To his detriment, he doesn’t comprehend that Pinkie has no concept of friendship. And finally, there’s a visually lush contrast between Pinkie’s world — a rooming house with stale pastry crumbs on his bedroom floor, a wobbly banister along the stairs leading up to it and a diet consisting of sausage rolls — and the Louis Seize décor that surrounds Mr. Colleoni at the Cosmopolitan, the lavish cocktails, and the music drifting in from the Palm Room. Brighton Rock doesn’t focus on socio-economic class differences, but these are nonetheless present.

To Greene’s credit, these stark contrasts don’t produce two-dimensional characters. There’s plenty of complexity in each one. And when it comes to Pinkie, we’re left with the question: to what degree are we witnessing irredeemable sociopathy or to what extent is the seventeen year old boy a product of his life circumstances? We’re given snippets of his past that offer clues. He attended a boarding school and there are passing references to the cruelties that he had experienced there. He doesn’t have parents in his life — he’s alienated from them. But he viewed the recently killed Kite as something of a father figure, one that made him feel safe. What he does seems to stem from an all-encompassing threat perception. Pinkie’s faith leads him to hope that once he’s no longer engulfed by threats, he might return to the familiarity of the Church, finding peace and forgiveness, and the ability to turn his life around. He has no self-awareness of just how deeply maladjusted he really is. Pinkie’s evil deeds don’t happen in a vacuum. Greene sprinkles bits of context as the plot unfolds.

Greene writes with a cinematographer’s eye. That’s perhaps unsurprising considering how many of his books were turned into films, including Brighton Rock in 1948. Greene himself produced stories intended for the silver screen. Many scenes in this novel are exceptionally vivid. Among the most effective is the decidedly cold and unloving atmosphere of Rose and Pinkie’s civil wedding. The registry building, we read, is a “great institutional hall from which the corridors led off to deaths and births…there was a smell of disinfectant. The walls were tiled like a public lavatory…They sat down. A mop leant in a corner against a tiled wall. The footsteps of a clerk squealed on the icy paving down another passage.” Greene demonstrates a remarkable ability to make a wedding feel clinical. To add to the hopelessness of the wedding, Pinkie doesn’t even produce a wedding ring, much to the disgust of the registrar.

The marriage had to be arranged by Pinkie’s corrupt lawyer as both of the teenagers were under age to be legally wed. Rose struggles to reconcile her commitment to Pinkie — as well as how much she looks up to him — with their shared belief that they are engaging in mortal sin, and thus signing off on their own damnation. Pinkie sees the marriage as little more than a transaction, ensuring that Rose couldn’t be asked to serve as a witness and to testify against him for what he did to Fred Hale. But the sad wedding doesn’t bring him any relief. He’s repulsed by the idea of a wedding night and consummating the marriage. He also wonders if saving himself from earthly justice is short-sighted, given that it means an eternity of suffering. Here, we read: “He stood back and watched Rose awkwardly sign — his temporal safety in return for two immortalities of pain. He had no doubt whatever that this was mortal sin, and he was filled with a kind of gloomy hilarity and pride. He saw himself now as a full grown man for whom the angels wept.”

Brighton Rock explores the concept of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ from a more earthly perspective — represented by Ida’s crusade to bring Pinkie to justice and to rescue Rose — and the idea of good versus evil, from a transcendent vantage point, as embodied by the young couple. But with its strong religious undertones, can Greene’s novel still have something to say to more secular readers today? The Catholic scrupulosity demonstrated by Rose and in many ways by Pinkie may seem foreign and eccentric to a post-Christian or non-Catholic readership. Yet even today, people continue to wrestle with matters of conscience. The vocabulary and the imagery might be different for many, but the existence of objective evil is still recognized. People struggle to understand its persistent presence and the horrid suffering that it causes. One of the most memorable lines in the novel is spoken by a nameless old priest, who sits in a confessional box with a head cold, smelling of eucalyptus. Although congested, he speaks with clarity: “You can’t conceive, nor can I, or anyone the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God.”

In some ways, he’s speaking directly to the reader of this sometimes strange novel. Greene’s story is one that portrays the mystery and the madness that is part of human existence.

Yet another great review, Chris! I am curious now about why the mobsters wanted to kill Fred, i’m also interested in pinkie’s backstory and the root cause of his attitude towards love and friendship. Without knowing The reason for Fred’s death makes it hard for me to understand the connection between Fred and Pinkie. Pinkie is described as a sociopathic gangster with no interest or regard for life or love, which makes me wonder if he was born like that or if life conditioned him to be that way, which you mention later on. I’m interested in reading some of the passages narrating the time he spends with Rose due to his clear disregard for such relationships. I find it funny how someone who doesn’t believe in love ends up getting married just to ensure his safety from prosecution. This book has many religious aspects and undertones, and thoroughly explores each main character’s beliefs, opinions, and practices. Pinkie’s view of Hell is formed based on his life experiences and the things he has done due to his lack of safety and security, which is relatable to many people today. When Ida attends Fred’s Funeral she second guesses her faith and beliefs, which is also very relatable. Many people disregard religion and life after death because they would rather have fun and party, until death touches them or someone they know. This novel explores many different views and personalities and blends them all together perfectly, and based on your commentary I believe that the author had his own personal thoughts on what exactly defines right and wrong. Brighton Rock is definitely going on my reading list.

[…] Porter’s description of Margaret Laurence as being shy, empathetic and having a fierce sense of morality didn’t surprise me. It’s exactly the impression I got years ago after watching the lyrical 1978 National Film Board of Canada documentary Margaret Laurence — The First Lady of Manawaka, and a shorter NFB piece from 1985 entitled A Writer in the Nuclear Age. In both pieces, Laurence’s compassion and sense of justice elicits a fiery, passionate response when she witnesses injustice. She’s furious when a group of Fundamentalist Christians moves to get her book The Diviners banned from Ontario schools, even though it’s evident from her work that she has a clear and strong moral compass — while not being afraid to acknowledge and present that evil exists in the world. I learned from Porter that Laurence appreciated the books of Graham Greene — the British twentieth century author who so often drew from the wells of conscience, moral dilemma and grace. […]