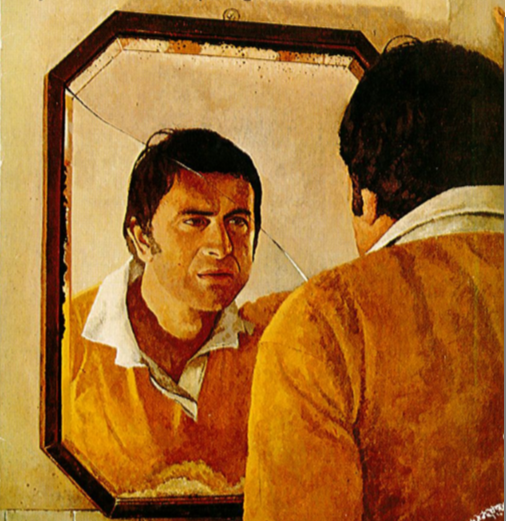

Terse, aloof, cold, almost completely devoid of intimacy–this is how I would describe much of the dialogue in British novelist David Storey’s 1972 book Pasmore. The narrative, heavy on clipped dialogue, explores the mental unraveling of the 30 year old protagonist. Colin Pasmore is a university lecturer living and working in the London boroughs of Camden and Islington. He has a comfortable middle-class existence, a wife and three loving children. With a good career and a family, one would think that he ought to be satisfied with his lot in life. Yet Pasmore is not only profoundly unhappy with both his professional and personal life, but his behaviour alienates him from his family, friends and colleagues.

In an effort to escape his life, Pasmore rents a room and begins an affair with an enigmatic and remote woman called Helen. She too is married and she turns being blasé and having a stiff upper-lip into a veritable art form. The only warmth that seems to exist is the cozy fireplace in Pasmore’s rented quarters. Pasmore’s adulterous relationship with Helen, however, lacks even a trace of affection and feels mostly like a cold business transaction. After their meetings, Pasmore often asks Helen if he will see her again and her response is simply “if you think it’s worth it.”

Even painful scenes in Storey’s book are mostly relayed using economical and restrained language. When Pasmore leaves his wife Kay without even telling her or their children where he will be staying, we read: “All that he was really aware of in leaving home was the children’s faces: not knowing where he was going, nor for how long, they waved cheerfully at him from the front-room window.”

As could be expected, Pasmore’s relationship with Helen does not last. As his marriage falls apart and he becomes unwelcome in his own house and a stranger in the eyes of his children, Pasmore journeys home to his parents to tell them the difficult news in person. We learn that Pasmore comes from a working class family and life for his father, a miner in an industrial northern town, is merciless. With a sister who is a socialist politician, a father who spends most of his life underground, in mines, and the backdrop of life in grim council estates, Storey gives his readers a poignant glimpse into, and commentary on class-based realities in early 1970’s Britain. The language in the latter half of the novel seems to become a little less terse, although hardly verbose. Above all, however, the author’s use of language is effective. For instance, the daily, unchanging misery experienced by Pasmore’s father is described like this:

He watched his father go off towards the black buildings near the shaft. As he neared them, he turned around, his face lit up by the orange flares. He nodded then turned, glancing round at the other men then disappeared. The sky had cleared. The sun shone down across the wheatfields, yellow, almost orange, laid out between the pits. Somewhere, underneath, was his father, lying down.

Although Camden in the seventies is a world apart from the gritty industrial north, it’s not at all the Camden of today, much like London then was fairly dowdy and staid when compared to the international metropolis that it is now. We see the issue of class enter into Pasmore’s world in London too, as he peers out from the window of his rented quarters: “In the evenings, from between the curtains, he would watch the figures collecting in the street below, the scavengers and outcasts, an army of degenerates about to haul him down.” Here what we get is the fusion of Pasmore’s isolation, as a result of being mentally unwell, and a reminder of his own social background.

There’s a great deal in Storey’s novel that goes unsaid, at least in an explicit sense. Yet the careful reader knows precisely what’s going on and what the various characters are really thinking just by the author’s masterful, if economical, use of language in the dialogues. The novel is also a reminder that mental illness can exist even within those in society who would appear to be living an ideal life.

Be First to Comment