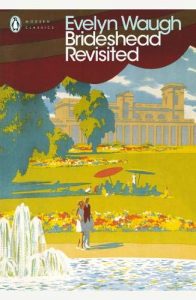

British novelist Evelyn Waugh was what one might call a traditional Catholic and Catholicism is central to his 1945 novel Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder. Waugh was outright despondent following the liturgical transformations of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and felt as though he was losing the church and faith that he embraced after his conversion in 1930. What is so paradoxical about all we know of Waugh’s Catholic faith and the treatment of Catholicism in Brideshead Revisited is that the book is at times quite irreverent and at its heart is a romantic relationship between two young men: the narrator, Charles Ryder, and Lord Sebastian Flyte.

Charles and Sebastian are undergraduate students in the early 1920’s when they meet at Oxford University. Although they are from different social classes (Charles is from the upper middle class, while Sebastian is aristocracy), they share one thing in common: both come from unhappy, dysfunctional families. Charles’ mother had died and his father is socially awkward and highly introverted, taking only marginal interest in his son. Lord Sebastian also comes from a broken family. His parents are separated and his mother, Lady Marchmain, a lonely, frustrated and tragic figure who tries mostly in vain to pass on her staunch Roman Catholicism to her children, is a suffocating presence for the young Sebastian.

In the first part of the book, Sebastian is portrayed as flamboyant, careless, lively and eccentric. He walks around Oxford carrying a teddy bear named Aloysius who, we are told, is prone to acting out and has an attitude. Lord Sebastian even acquired a brush with stiff bristles, with the teddy bear’s name engraved on it, in order to “threaten him with a spanking when he was sulky.” Whether the teddy bear took those threats seriously was another matter. In one of his first notes to Charles, inviting him for lunch, Lord Sebastian writes, after having been drunk the night before and vomiting out of Charles’ dorm room window: “I am very contrite. Aloysius won’t speak to me until he sees I am forgiven, so please come to luncheon today.” As Charles Ryder observes upon first seeing Sebastian at Oxford: “He was the most conspicuous man of his year by reason of his beauty, which was arresting, and his eccentricities of behaviour, which seemed to know no bounds.”

For a book published in Britain in 1945, the romantic relationship between Charles and Sebastian is described in non-sensational, even “normalizing” terms. The Catholic Church would have seen such a relationship as sinful and “disordered,” and Waugh was very much a Catholic. Yet we have warm scenes with ornamental language in the book to describe the relationship, such as this: “Under a clump of elms we ate strawberries and drank the wine…and we lit fat Turkish cigarettes and lay on our backs, Sebastian’s eyes on the leaves above him, mine on his profile, while the blue-grey smoke rose, untroubled by any wind, to the blue-green shadows of foliage, and the sweet smell of tobacco merged with the sweet summer scents around us and the fumes of the sweet, golden wine seemed to lift us a finger’s breadth above the turf and hold us suspended…That day was the beginning of my friendship with Sebastian, and thus it came about, that morning in June, that I was lying beside him in the shade of the high elms watching the smoke from his lips drift up into the branches.”

As the book progresses, Sebastian transforms from being an exuberant, animated young man to an unhappy alcoholic who causes his mother to fret and to assign him to the care of a minder who abuses his position. Sebastian and Charles drift apart, and Charles ultimately begins a romantic relationship with Sebastian’s sister, Julia. Yet even then it seems clear that Charles’ attraction to Julia stems from his original love for Sebastian and the resemblance he detects between the two. When Julia asks Charles why he married a woman called Celia who he did not seem to love, the response is telling: “Physical attraction. Ambition. Everyone agrees she’s the ideal wife for a painter. Loneliness, missing Sebastian.” Julia then asks: “You loved him, didn’t you?” Charles responds candidly: “Oh yes, he was the forerunner.”

When Charles visits Sebastian in his new home in Morocco, where he is living with a man who clearly takes advantage of him financially, we get a striking glimpse into his unhappiness. Speaking about his dubious companion, Kurt, Sebastian tells Charles: “It’s a rather pleasant change when all your life you’ve had people looking after you, to have someone to look after yourself. Only of course it has to be someone pretty hopeless to need looking after by me.”

Loss and the nostalgia to which it gives rise is the central theme of Brideshead Revisited. And it’s loss on so many levels: a loss of physical and socio-cultural landscapes, a loss of youth, of relationships, of family, hope and of religious faith. It’s also believed that Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited is autobiographical on a number of fronts–certainly in terms of religion, the author’s embrace of a rich tapestry of tradition that finds expression in England’s privileged classes and his own relationships during his student years at Oxford and beyond.

[…] this theme is also present, indeed it is front-and-centre, in Waugh’s most celebrated book, Brideshead Revisited. In one episode, he thinks the passengers aboard the Caliban are gossiping about […]

Based on my reading of Christopher’s review, traces of religion can be found throughout the book, and a lot of sexuality that would no doubt have been frowned upon at best at the time can be observed as well. We can also see that there is a significant amount of loss to be had for many characters in the book. We see nowadays that there is still some discrimination against homosexuality, but it doesn’t hold a candle to the type of discrimination that homosexuals faced in the time that ‘Brideshead Revisited’ was written. To me it seems pretty edgy for the time, and especially so learning how devoted to Catholicism Waugh was. Class separation is another theme we can observe here and seems to be pretty common in the reviews of Waugh’s novels. We can only assume that this particular recurring theme must have been the result of the times in which Waugh lived- and its overtness the result of the times in which we live.