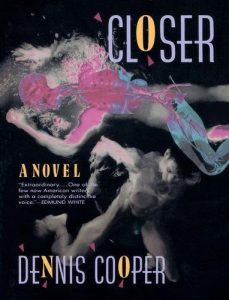

There is barely an ember of warmth in Dennis Cooper’s work of transgressive fiction Closer. Instead, we meet a handful of young men on the threshold of adulthood who seem emotionally detached from any sense of community, family or from the concept of human dignity. It’s almost as if they exist as merely biological bodies–vessels devoid of that which actually makes us human. As such, an intrinsic sense of compassion for the other and respect for oneself is also mostly missing in his novel and we are presented with acts of degradation and exploitation perpetrated against others, and emotionally scarring sexual activity that shocks the reader but leaves the characters in this book largely unmoved.

Each chapter in Closer is told from the perspective of a new character. What bridges each chapter into a coherent narrative is George Miles — a high school student who finds himself at the centre of attention of everyone in the novel. The common thread is the vulnerability of George Miles and how his peers take advantage of him. He’s not a fully developed character in this book (which is the first in a series of five novels built around George), but it’s hard not to empathize with him, based on what we do know. For one, his mother is extremely ill and so the only source of parental stability comes from his father. Second, he is trying to understand and come to terms with his identity as a gay teenager in the 1980’s.

The emotional emptiness is emphasized by how some of the characters see and describe themselves, and how they are seen by others. Frequently, we don’t see the person as such, but rather only his shadow, his reflection or a mask that someone else places on him. For instance, the young David is a popular singer and is famous for his physical appeal. In the context of one of his photo shoots, we read:

I can’t see the face of the man who’s been hired to perfect me, only a small piece of convex glass, in which I come face-to-face with my distorted reflection. I look kind of faint. Still, its contours soothes me like nothing else…The photographer won’t stop perfecting me. He says ‘smile,’ I smile. He says “Look sexy,” I try. He just announced that I look too emotional. I think ‘How is that possible?.’ I say ‘I’m sorry.’ I close my eyes for a time, then shake my head violently side to side. This succeeds in emptying out my expression…The photographer puts down his camera, walks up to me, takes a hand mirror out of his pocket and makes up two lines of cocaine, which I snort, then smile into his lens again, my eyes ecstatic and glittery, like they’re reflecting a million children’s.

In some ways, Closer is a coming of age story, perhaps a little reminiscent of novels like the iconic Catcher in the Rye. But rather than maturing emotionally and intellectually, and growing into adulthood, life seems to rather deform the young men who inhabit these stories. As these young men age, they are increasingly detached from their humanity and the humanity that one would think (or hope) is inherent in society around them. In David’s story, his youth and also his innocence is robbed from him through vacuous stardom and the sexual assault he suffered at the hands of an adult. At times, Cooper uses haunting imagery to underscore this detachment and dehumanization, such as the story of John, a fledgling artist who becomes preoccupied with capturing George Miles in portraits. We read: “On the way home from school, John took a detour so he could walk through the park. The usual ghosts of themselves were throwing balls in slow motion down corridors marked on the lawn…”

In this story of John’s obsessive and sexually charged mission to draw George, there are obvious parallels to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and there is one overt mention to the late nineteenth century classic that once scandalized audiences. We read: “The real goal of my work is a Dorian Gray type of thing. I make you look awful, and I start to look really good.” While Cooper’s concept builds on Wilde, it’s also a somewhat purposeful distortion of Dorian Gray. Wilde dwells on human beauty using ornate language, which also serves as a device to communicate indirectly the same-sex nature of the relationships being explored in this Victorian novel. With Cooper, we have fairly terse language, often explicit acts of sexual exploitation and an exploration of the physical that is more dehumanizing than beautiful. In one sexual encounter, this is apparent in an especially stark way: “We become two little ghosts wearing human masks, nothing to look at below the neck…I hate the fact that human bodies are warm. I think they should either be ice cold or have no temperature whatsoever, like pieces of paper.”

In some ways, Closer is very much an eighties novel — building, as it does, on the punk subculture of the time, but also a sense of youth disillusionment with mainstream suburban society. At times, I had the British ensemble Dead Or Live’s song “You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)” playing in my head as I read, and other occasions it was Pink Floyd’s “We Don’t Need No Education.” Ultimately, however, this novel isn’t a nostalgia trip for those who may have been around, or were young children, or were otherwise connected to the eighties. In plain language and with a simple story structure, we get what is ultimately a difficult and disquieting read.

Be First to Comment