Repulsed by the judgmental attitudes and bigotry of his church, and experiencing a crisis of faith, Pentecostal pastor Asher Sharp decides that plunging into the unknown is more life-giving than sticking with the stability of home. The arrival of two gay men to his Tennessee town and the Christian community’s homophobia compel Asher to confront his wife and church, as well as the chasm between the Gospel message as it is interpreted by his congregation and the complexities of the lived human experience.

The novel opens with a great flood; one which decimates this little town along the Cumberland River in Tennessee. While Pastor Sharp visits and tries to comfort members of his congregation who have lost everything, his wife Lydia prays fervently and unceasingly in her house. Asher can’t get himself to join her in prayer and there appears to be distanciation between the two. As the story unfolds, we learn how Asher’s rejection of his gay brother Luke many years ago, stemming from his own personal religious convictions and a desire to appeal to the virulent homophobia of both his wife and his abusive late mother, has left him guilt-ridden. When the strangers in their midst display heroism in trying to save and assist locals during the flood, yet are turned away as soon as their relationship and sexuality become clear, Asher seems to reach the end of his rope. His willingness to welcome the men into his church scandalizes his congregation and the deacons fire him as pastor.

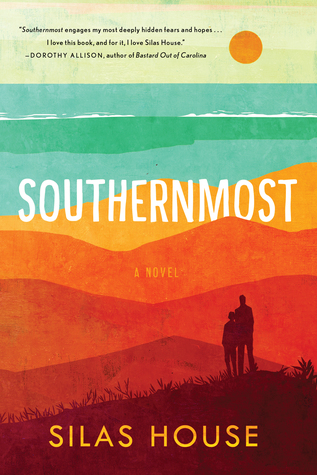

After Asher gives an impassioned and emotional plea from the pulpit to replace judgment with hospitality, he divorces his wife and loses custody of his nine year old son Justin. Southernmost is set against homophobic backlash in Tennessee against the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on same-sex marriage; it is a state where prejudice appears to influence the justice system. Somewhat ironically, given how accustomed Pentecostals are to appeals to emotion and to catharsis, Asher’s passionate defense of inclusion is enough to convince his congregation and later the judge that he is unstable and therefore unable to care for his son. This is not a verdict that Asher can accept, nor does he trust in the possibility of an appeal. As such, he kidnaps his son from his mother-in-law’s home and the two make the grueling drive to Key West, Florida, where he hopes to find his estranged brother.

Does Silas House’s novel present a dichotomy between an inclusive, enlightened secular world and regressive, prejudiced organized religion? Early in the novel, it does feel at times as though this was the novel’s overall direction. Yet right when I was prepared to draw this conclusion, House provides examples of more introspective religious thought. Fittingly for an author from Kentucky, House makes references to Catholic theologian and monk Thomas Merton, who lived at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, a Trappist monastery in a rural region of the state. Asher’s estranged brother Luke quotes Merton when he writes on a postcard: “Everything that is, is holy.” There is a line of theological thinking which emphasizes that the entire living world is suspended in existence by God, including people who find themselves rejected by churches that are quick to judge and condemn. House’s book also engages, implicitly, with the concept that life itself, especially when lived charitably, is prayer, and that churches cannot circumscribe the divine. In an interview on the author’s own faith, we learn that House is a member of the Episcopal Church. Part of his book reminded me of the theology of Episcopal priest Barbara Brown Taylor’s pastoral work An altar in the World. As well, Asher’s employer and landlady in Key West, the crusty, straight-talking, but compassionate Bell is herself an Episcopalian who rarely leaves her home and receives weekly communion during pastoral visits. And at various points, Asher and his son discover something transcendental in the natural world that surrounds them.

Southernmost’s language is smooth and evocative, and the narrative arc builds naturally. The protagonist, his son and the people they meet in Key West have a depth and dimension that is revealed to the reader gradually; much more depth than most of the people left behind in small-town Tennessee. While this is first and foremost a story of escape, fatherhood and sacrifice, the novel’s overarching challenge is to consider what we’re willing to risk and give up in order to find that which is life-giving.

Be First to Comment