Muriel Spark’s 1988 novel — a drama, a mystery and a comedy in approximately equal measure — is in some ways a nostalgic, yet unsanitised reflection on the London publishing industry of the fifties. We travel back to postwar London, still pockmarked by the Second World War. Our guide on this journey is Mrs. Hawkins — an ageing insomniac in the 1980s who enjoys listening to the silence of the night. As the narrator, she reflects on when she was a 28 year old war widow in 1954-1955, working as an editor and proofreader for British publishers. Employing a conversational tone, she also takes the liberty of sharing various pieces of advice with the reader — most notably, how to lose weight by simply eating half of every meal and how a novice author ought to approach writing a debut novel.

Mrs. Hawkins is the story’s anchor in more ways than one. For nearly the entire novel, we know her only as Mrs. Hawkins. Later, she consents to being called Nancy. She’s a dependable and stable Anglo-Catholic woman to whom flighty, anxious and otherwise troubled people turn to for advice and sound opinions. She has a no-nonsense persona and she’s principled to the point that she sometimes pays a price for it. At noon, she recites the Angelus. The words of prayer in her head are comically interspersed with her straight talk, as she’s usually speaking with someone at that hour and standing her ground. Mrs. Hawkins looks and acts older than her young age, she acknowledges her obesity and for most of the book, doesn’t show much interest in dating.

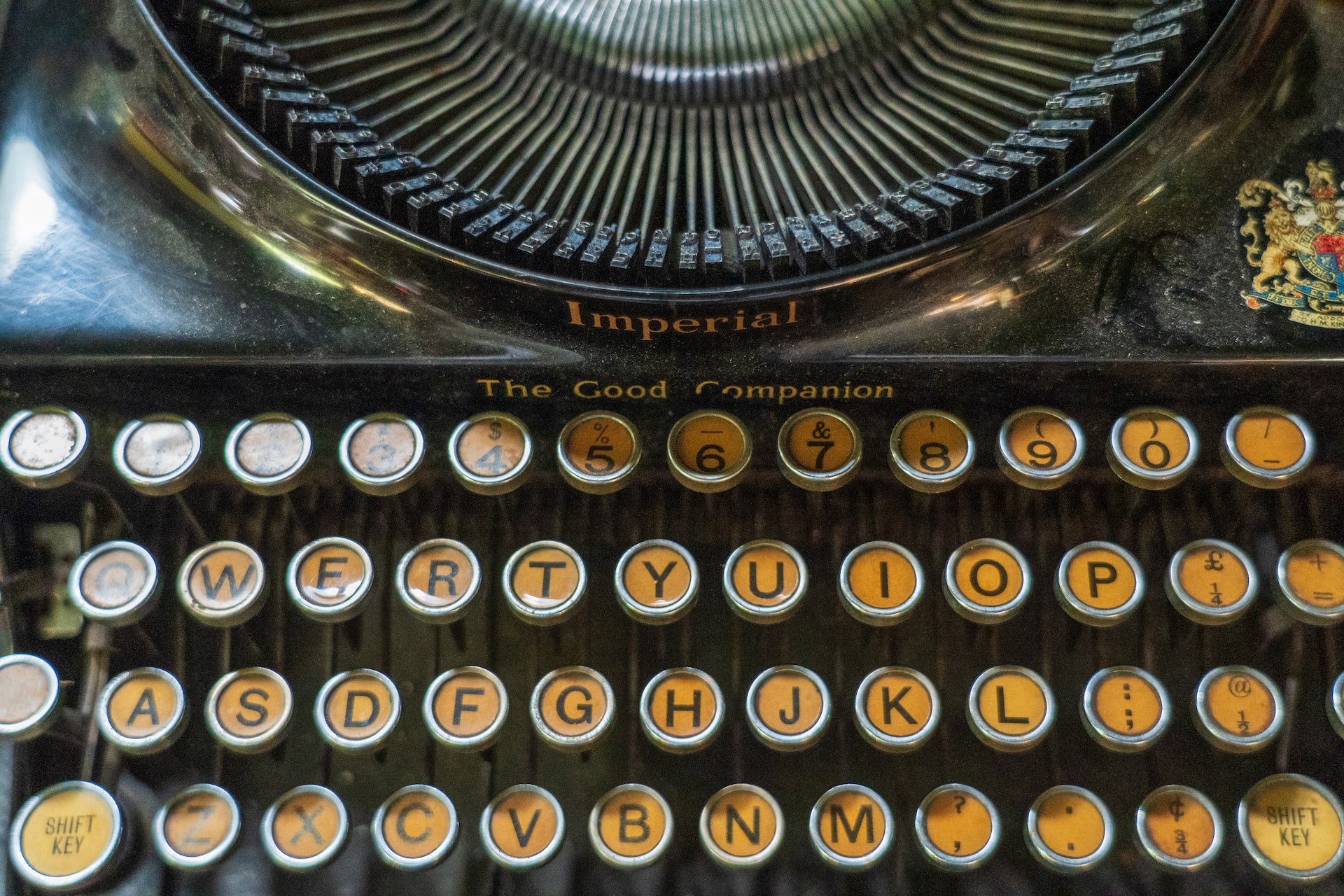

The world depicted by Mrs. Hawkins has no shortage of eccentric publishers, untalented authors with oversized egos, a small handful of successful authors who enjoy (and expect) preferential treatment, and editors struggling to get through the slush pile of unread, unsolicited manuscripts on their desk. In some cases, editors farm out to freelance readers across Britain the review and rejection of these manuscripts. That’s a luxury far less common in today’s more meagre publishing industry. Otherwise I think many editors, literary agents and publishers could read A Far Cry from Kensington and say to themselves: plus ça change…

One of the more memorable lines in the book is from Mrs. Hawkins’ interaction with a minor character at a London publishing house. We read:

‘The best author is a dead author.’ And it is true we would have an easier time if we only had the books to deal with and no live authors; Mackintosh & Tooley had a small back-list of dead writers who caused very little trouble (except occasionally through their heirs and executors who got taken out to lunch if they became too difficult)…’Books don’t wriggle. Authors do,’ was one of Colin Shoe’s remarks. ‘They take everything personally.’

At the heart of the book and Mrs. Hawkins’ troubles is the hack author, poser and social climber Hector Bartlett. Mrs. Hawkins mercilessly labels him a pisseur de copie — “a urinator of journalistic copy” — including to his face. Mrs. Hawkins doesn’t hold back when she observes that Bartlett “vomited literary matter, he urinated and sweated, he excreted it.” Bartlett is the one person in the novel who seems to truly get Mrs. Hawkins enraged. And he does, in fact, prove to be a despicable character.

When Mrs. Hawkins labels him with her offensive epithet, she gets fired from the nearly bankrupt publishing house for which she works. Bartlett has no weight as such, but he’s friends with a successful author, Emma Loy, who can pull strings in the industry. Mrs. Hawkins’ termination is no tragedy, as the firm for which she worked was a sinking ship with the publisher, Martin York, facing fraud charges. Unfortunately for Mrs. Hawkins, Bartlett’s long and irritating shadow follows her even when she’s hired by a larger, more reputable publisher. He is like a rash on the face of London’s publishing industry– and one that won’t go away.

The publishers in this novel are scattered and eccentric individuals. Martin York often awards book deals out of loyalty to friends, while engaged in clumsy attempts at fraud. When Mrs. Hawkins gets hired by the much more respectable firm Mackintosh & Tooley, Ian Tooley turns out to be a Spiritualist who is more interested in Horoscopes and “curing” ailments remotely by collecting fragments of hair and putting them in a magic box than in publishing books. One of the funniest scenes in the novel is Mrs. Hawkins’ interview, which wasn’t much of a traditional job interview at all.

In addition to the world of publishing, Mrs. Hawkins introduces us to London’s Victorian era bed-sits, specifically one located in South Kensington. She lives in what we might call a rooming house, although it’s not quite what we may have in mind. The landlady, Milly, rents out rooms and makes tea for a diverse group of residents: a germophobe nurse, an anxious and diligent Polish immigrant dressmaker called Wanda, a medical student, a spoiled and flaky university student from a privileged background, and a young couple. Milly and Mrs. Hawkins have a good, trusting relationship, as the landlady often turns to her for advice.

In her narrative, Spark expertly ties together these two very separate worlds — the bed-sit and its characters, and the world of publishing and its personalities. For a relatively short novel, there are in fact many characters. Some of them are quite fleeting. But even the minor ones either reveal something important to the plot or else help recreate the 1950s environment.

Having read and reviewed Spark’s Memento Mori a few months ago, it’s tempting to compare the two. Memento Mori was written in 1959, early in Spark’s career, as her third novel. It explored the fifties in London not from retrospect, but from the thick of it, so to speak. It’s also a harsher book. Spark’s writing always has bite, but of these two novels, Memento Mori has much more. It also seemed to me, as far as I can tell from the written word, that the characters in A Far Cry from Kensington used less Received Pronunciation. They are a younger set than the personalities in Memento Mori. This was among Spark’s last novels.

It’s clear that much in A Far Cry from Kensington is based on Spark’s own life experience – including as an editor in the same era. She was also someone known to keep absolutely meticulous notes on everything, just in case someone in the literary world attempted to stab her in the back. Literary revenge is the vehicle through which Spark explores the face of morality and immorality in this story. And what’s clear in the novel is that in Spark’s presentation, the jail-bound fraudster publisher, Martin York, is more ethical than many others in the industry. A Far Cry from Kensington is in many ways an entertaining read, but it isn’t an entertainment. Spark’s works are always more reflective than that.

A Far Cry From Kensington, based on your description, seems to be an interesting narrative. I am always impressed by the way in which you are able to give a novel an intriguing review, providing the exact amount of detail required to spark my interest. As a young person who has a strong interest in written works, literary art, and history, I can one hundred percent say that this novel is yet another great book I would have never discovered without this webpage. After reading your review, I’m interested to know if the publishing world of today has as many eccentric characters as the industry seems to have had in Britain circa 1955.

As for the disdain Mrs. Hawkins feels for Mr. Bartlett, I’m curious as to what the initial encounter or behaviour she observed was. I also would have liked to been given a brief glance at the comical job interview. You claim that the novel has a strange balance of drama, mystery, and comedy, but did not exactly include any examples. I am aware of the fact that when providing commentary on a book, movie, play etc. that nobody wishes to include any “spoilers” which is everybody’s preferred method, but I can’t lie by saying I would have enjoyed a little appetizer in this regard. All in all I can say that the commentary you provided has piqued my interest in not only this novel, but the world in which it is set, as well as the time in which it takes place. Please continue to expose myself and all of your other readers to more of these hidden gems.